(back row, l-r) Jacob Desmond, Steve Swihart, Elaine Guinn, Walt Keller, and Mike Long; (front row, l-r) Lillian Henegar, Kevin Bruce, and Jackie Daniels; photographed in the lobby of SpringHill Suites by Marriott Bloomington. Photos by Rodney Margison

BY CARMEN SIERING

PHOTOGRAPHY BY RODNEY MARGISON

The summer of 2017 saw a wave of opioid overdoses make headlines in Bloomington, and it became increasingly impossible to ignore the impact this epidemic is having on our communities. Task forces were established and new treatment centers have been proposed.

But even as we begin to address the problems of illicit drug and prescription medication addiction, new studies are shedding light on an even more prevalent problem—an increase in the misuse of and addiction to alcohol.

According to a new study published in JAMA Psychiatry, several signs of alcohol misuse are on the rise, leading to the startling conclusion that as many as one in eight American adults—12.7 percent of the population—meets the diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorder. And while a 2016 Surgeon General’s report noted there were 47,055 drug overdose deaths in 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that from 2006 to 2010, alcohol was linked to 88,000 deaths per year. A failure to recognize alcohol as a drug is obviously naïve—and dangerous.

Unfortunately, whether the addiction is to drugs or alcohol, we have come to expect those who are addicted or in recovery to stay silent about what has long been recognized as a medical disorder. Addiction is as much an illness as heart disease or diabetes, and yet it is still often treated as a crime (in the case of drug addiction) or a moral failing (in the case of alcohol addiction). In fact, addiction is a chronic health condition, one that can be controlled through long-term recovery.

Like the increase in awareness about breast cancer in the 1970s (in part due to first lady Betty Ford’s openness about her mastectomy) and the often radical push for HIV/AIDS awareness in the 1980s, there is now a growing addiction recovery movement that seeks to pull it from the shadows of guilt, shame, and stigma. While respecting the traditions of anonymity surrounding many recovery programs, there are now people in recovery who feel it is time to start discussing addiction honestly and openly as an illness and a public health issue.

The men and women featured here came to Bloom and asked if we would publish their stories. They are eight of the more than 23 million Americans in long-term recovery. Their shame vanquished, they hope their stories will inspire others who are suffering to seek help. We hope so, too.

Kevin Bruce.

Kevin Bruce

English as a second language tutor; serves on the board of Amethyst House

Sobriety Date: May 2, 2009

Why he shared his story: “The uplift one gets from being around others in recovery can’t be captured in print, but we still try. I know that alcohol is addictive to me and I share the same pathway as anyone else on an addictive pathway.”

When he was 6 years old, Kevin Bruce suffered from rheumatic fever and was confined to bed for six months. “Once I got out of bed, I didn’t have any muscle tone, and my parents carried me around by the shoulders until I could walk,” he says. “But the doctors said no running or climbing stairs until I was 12.” This singled him out from the other boys in his central Massachusetts town. Instead of learning sports, Kevin says, he spent his time reading and dreaming about exotic locations around the world.

His exposure to addictive substances growing up was somewhat typical—pilfered cigarettes and alcohol as a young teen, greater amounts purchased illegally when he was older. It wasn’t until he went to college that it became clear he was becoming addicted.

In 1962, Kevin was accepted at Brown University. He says he chose Brown, in part, because his older brother went there. But also because, he says, “Underage drinking was a matter of course and part of the culture.”

Drinking soon affected his academic performance. “Still, when I consulted a school psychologist, we discussed my grades and the lack of interest my father had in them and how that might affect my achievement,” he says. “But we never discussed alcohol.”

As graduation approached, those childhood dreams of exotic locations came into focus—especially as a more horrifying possibility loomed. “This was during the Vietnam War,” Kevin says. “I didn’t want to get killed and I didn’t want to kill.” He and his girlfriend, Barbara, married and joined the Peace Corps. They were stationed in Micronesia where they taught English and did community development work.

“Once we settled on our island with 500 people, it got pretty quiet and slow,” Kevin says. “Drinking was a comfort.” He brought a case of Scotch whiskey from the main island. When that ran out, local brew was satisfactory. “The natives had been taught by the Navy how to make alcohol with yeast and sugar and fruit or coffee,” he says. “Within 24 hours, it was drinkable. But the hangovers were absolutely wicked.”

The couple returned to the U.S. in 1968, and found that Kevin could continue to avoid the draft by teaching English in the inner city. While they faced many challenges, they gained something valuable, too. “In 1970, we became immersed in yoga,” Kevin says, “and found relief from alcohol and tobacco.”

Their interest in yoga led them to move to Spain, where they lived for eight years in an orange grove, grew their own organic food, and taught yoga and meditation.

But in 1978, they returned to the U.S. and Kevin started teaching at his hometown junior high school. It was a rough transition. “Once I got back to America, I slipped away from yoga and I started to smoke and drink again,” Kevin says. “I would call it PTSD after eight years of simple living.” Sensing a problem, two years later he and Barbara joined the Bruderhof, an intentional Christian community in New York’s Hudson Valley. They lived there for 22 years, raising four daughters. In 2002, they left to allow their daughters to experience a broader vision of life.

Over the years, Kevin says he drank or didn’t, depending on circumstances. For example, during a six-month teaching stint in India, he was sober. “I knew I had a family I was responsible for, and young people I had to be an example to,” he says.

By 2009, Kevin was teaching at a community college in Ohio. “And I was drinking again,” he says. But that was the end. “I got fired from the college for my drinking,” he says. “And finally, for me, it was hitting bottom.”

That was eight years ago. Kevin takes a holistic approach to recovery, focusing on diet and yoga and meditation. “And just like I need yoga classes to keep my yoga moving forward, I need my recovery meetings and fellowship to keep my recovery moving forward,” he says. “I’m clear at last. It really begins with admitting to oneself and one’s partner that, on my own, I can’t make it.”

Jackie Daniels.

Jackie Daniels

Executive Director and Clinical Director,

Indiana Center for Recovery

Sobriety Date: Dec. 15, 2000

Why she shared her story: “This story highlights that there are people who are successful at recovery. There’s a saying in recovery—you’re only as sick as your secrets. So I’m doing it for myself, but I’m also doing it to show other people that it’s possible. I feel like a lot of people in recovery want to hide because of stigma and shame. And there’s nothing to be ashamed of.”

As the executive director and clinical director of the new Indiana Center for Recovery in Bloomington, it’s clear that Jackie Daniels knows a lot about addiction and recovery. Before she accepted her new position in May, she had served for five years as the director of OASIS, Indiana University’s student alcohol and drug support center. But Jackie’s experience with addiction is more personal than that, and it started early.

She says she had a typical American upbringing. “Two married parents, a sibling, a dog,” she says. “I had a great family, great resources, and all I could ever need. And with all of that, I still have an addiction. So that destroys the myth about the kinds of people who end up with an addiction.”

Describing herself as a thrill-seeking child, Jackie says that by middle school she was experimenting with drinking. “My parents didn’t know. Nobody knew,” she says. “Because I thought it was shameful. So I did it when I was alone.”

Her parents did sense something, though, and sent her to a boarding school for high school. “That’s one of the best decisions they ever made for me,” she says. “I excelled there.”

New Year’s Eve her freshman year, she tried champagne for the first time. “I couldn’t stop until I finished two bottles,” she says. “I vomited red slushy all over the floor. I thought I was hemorrhaging, and as awful as it was, all I could think was, ‘When can I do this again?’”

She says the one thing she learned from the experience was that if she ever got drunk again, she wouldn’t let anyone find out.

Things changed when she entered college in the fall of 1996. “When I got to IU, I kind of made a decision that I wasn’t going to hide it anymore,” Jackie says. “I was in an environment where it was okay to party. I started smoking pot. I got a prescription of opiates. So for me, addiction was alcohol, pot, and prescription drugs of various types.”

By fall 1999, addiction was affecting her life. “I got into an accident that was related to alcohol consumption,” she says. “I got a phone call from the prosecutor because I wrote a lot of bad checks to buy alcohol. At the time, I couldn’t see I was being dishonest or deceptive, I just knew I really needed it.”

In February 2000, she overdosed on prescription drugs and alcohol. “By this time, I was isolated,” she says. “My friends weren’t around to police me. I was drinking rum and taking pills to get high, and when I blacked out, I had thoughts of, ‘Whatever. If I die, nothing’s going according to my life plan anyway.’”

Somehow, she managed to call her mother, and woke the next day in the hospital. “I remember thinking, ‘Why am I waking up?’ I couldn’t understand why someone had intervened,” she says.

At this point, she went through an outpatient program but admits, “I was going out with all the people in the program to drink.” The fact that she was addicted wasn’t sinking in.

It wasn’t until she entered a two-month residential treatment program later that summer that she addressed her addiction. “They changed my perspective,” she says. “I realized that I had a different relationship with alcohol and drugs than other people, that I saw them as a solution rather than a problem.”

In 2001, Jackie returned to college, earned her undergraduate degree, and applied to a graduate program in social work. “I became very passionate about learning,” she says. “And I took my recovery with me. People would ask, ‘Why do you talk about recovery all the time?’ And I would say, ‘Well . . .’ And then I would say I was a person in recovery. Recovery is my life.”

At 39, Jackie has been in recovery for 17 years. “I’m passionate about life in recovery,” she says. “What we’re seeing in the news, in public policy, is that addiction is about race and poverty. It’s just not true. There are many different types of people affected. And we don’t get to share the fact that people do recover. So I’m passionate about shaping new folks in our field to treat others with compassion and about advocating for the elimination of the stigma surrounding addiction.”

Walt Keller.

Walt Keller

Licensed Clinical Psychologist

Sobriety Date: January 22, 1984

Why he shared his story: “I think it’s good for people who might be interested in recovery to hear from someone who might see recovery in a different way, to hear from someone in long-term recovery, and to know that all kinds of people are in recovery. As a professional, I think it’s important for me to speak up and share my story.”

If there is one thing that being in recovery means to Walt Keller, it means he believes. Before he was in recovery, when he was still addicted to alcohol and thought he always would be, he says he didn’t believe in anything at all.

“What was happening to me went beyond drinking,” says Walt, a licensed clinical psychologist retired from private practice. “I was raised Catholic. I knew right from wrong. But I didn’t care. I had always been the guy who paid his bills, who did the right thing. But at some point I just cut loose. I think I lost track of my moral compass.”

As an Indianapolis inner-city teenager in the 1960s, Walt says he was a product of his environment. “The first time I got drunk I was 16,” he says. “I got drunk and I threw up in a public place. About that same time, I went to jail. I got suspended from classes. I was banned from prom. I flunked five out of six subjects. And you know what I was? I was cool. That shows what that culture was like. And in that culture, if you were a man, you drank.”

Married at 17, he had two children within a year of being married, then a third. He worked hard—at a butter factory, a meatpacking plant, digging alleys. At one point he started going to college at night. “I was working full time, going to school full time, and my wife was working time and a half,” he says. They realized working and attending college would be easier in Bloomington. “We came to Indiana University, moved into married housing, and got financial aid,” Walt says. “After we paid rent, utilities, tuition, books, and fees, we still had a little bit left over.”

The family moved on to the University of Rochester in New York state, where Walt pursued his doctorate. Being in school was an ideal situation for Walt—it challenged him intellectually and it supported his drinking.

“I don’t know why, but I was always able to keep my drinking to a level where I could study,” he says. “But by grad school, I was getting blackout drunk.”

After grad school, Walt taught college for four years, then moved with his wife back to Bloomington in the late 1970s, where he worked as a clinical psychologist. At the time, he thought he was handling everything—marriage, work, partying all night—well enough.

“But I wasn’t doing as great a job as I thought I was,” he says. “I got a divorce. I drove back from Indianapolis in a blackout and ended up in jail. I got out of jail and drove straight to the liquor store. I used to be able to get drunk and just carry on. Now I was sitting on the couch in a stupor before the party even got started.”

The party ended in 1984. He says his last drunk wasn’t his worst drunk. It was just the one that woke him up to how bad things had gotten.

“I had lost faith in everything—people, institutions, the substances I was using to get me through it all,” he says. “It was easier to not believe in anything.”

He went into an intensive outpatient program. And that’s when he started to believe again.

“The very first thing that happened was that my skepticism lifted,” Walt says. “The other thing that happened was I fell in love with the process of recovery.”

That process, Walt says, is one of acceptance. “Addiction is a disease of denial and shame. It says I am not what I appear to be,” he says. “Recovery is about saying I am exactly what I appear to be.”

And yet, he says, we are so much more than we think we are. “Yes, I’m an alcoholic. And what else?’” he asks. “Since I was a little boy, you know what I wanted to be? Good. I’m Catholic, for God’s sake! I wanted to be good. So at every juncture in my life, I can ask, ‘What did I do that was good for other people?’”

He says that’s what recovery is about. “Recovery goes beyond my self-interest and into my contribution to humanity,” he says. “By losing self, we gain recovery.”

Walt says that through recovery, he’s gained acceptance. And through acceptance—of himself, of others—he’s found happiness. “I’m 71 years old and I’m happier than I’ve ever been in my entire life,” he says. “I just say, ‘Thank you, God, for this life.’”

Jacob Desmond.

Jacob Desmond

Graduate of Indiana University, May 2017; currently working and applying to medical school.

Sobriety Date: July 1, 2013

Why he shared his story: “I feel it’s my duty as a person in recovery to lessen the stigma assigned to those afflicted by drug and alcohol use disorder. I think [stories like this] help promote recovery and, hopefully, make recovery more accessible to our communities.”

Jacob Desmond remembers the first drink he ever took. “It was in the basement of my parents’ house in Carmel—a Diet Coke and Dewar’s whiskey in a large Steak ‘n Shake cup with a pink and white straw,” he says. “I was playing a Tony Hawk game on my PlayStation Portable and watching Anger Management on TV. This is all important because I can’t even tell you what I ate two days ago, so to remember something that vividly says there’s something unique and special about my relationship with alcohol.”

He was 12 years old at the time.

Drinking quickly became a part of Jacob’s daily life. “By the time I was 15, I was drinking before and after school,” he says. “I guess by high school, I was even drinking during school.”

Jacob, now 24, says he became very good at avoiding getting into trouble at school and with the local police, although he did get arrested his senior year at a party with a lot of other underage kids. “But I managed to graduate from high school—with honors, even,” he says. “I did have to retake my SATs, though, because I was hung over the first time.”

When he left for Indiana University, things were tense at home. He didn’t speak to his parents from the time he arrived on campus until he showed up again at Thanksgiving. “We were at odds with each other after high school and I think once I left, we were just taking a break,” he says.

IU was simply “more,” he says. “More alcohol, more of the party culture, more playing into the binge-drinking culture of Bloomington.” He calls that first year of college “a dark spiral” and, although he wasn’t speaking to his parents, when summer rolled around, they insisted he come home.

“My mom could see I looked bad,” he says. “She knew something was wrong. I talked to my parents about suicide that summer, generally when I was intoxicated. Finally, they staged an intervention.”

While the intervention included several people, and each one was supposed to read a story and then ask Jacob if he would consider going into treatment, it only took one person to speak before he agreed. “Most of my suicide discussions that summer were cries for help,” he says. “I was in a bad situation and I didn’t know how to get out of it.”

Treatment was a men’s retreat in Tennessee—33 days in the woods. From there, he moved directly to a halfway house in downtown Indianapolis. He took a semester off school, got a job, helped others, and started paying off his bills.

After that, he got an apartment in Indianapolis and took classes at IUPUI for a year, then re-enrolled at IU–Bloomington. When he did, he wanted to find a sober-living situation. “Ideally, I was looking for a student-run house where everyone was in substance abuse recovery,” he says. “There are a lot of them on college campuses across the United States.” But there are none at IU.

Instead, he connected with Jackie Daniels, who was, at that time, director of OASIS, the student campus alcohol and drug support center. Daniels helped Jacob and another student start Students in Recovery Bloomington (SIRB), a student-run, collegiate recovery program. Jacob and others also started a recovery support meeting specifically for young people. “That’s been helpful,” he says. “That’s the place where all of our buddies go.”

Jacob graduated from IU in May. He says he hopes the programs he helped start—SIRB and the recovery support meetings—keep going. But his focus is on filling out applications for medical school. He hopes to get accepted next year.

“I have every intention of trying to affect change as a physician,” he says. That’s a 180 for someone who once described himself as “cynical and reserved.” What turned him around? “I guess the ways I have seen my life change over the past four years have led me to be forever hopeful and optimistic,” Jacob says.

Lillian Henegar.

Lillian Henegar

Bloomington Township Trustee

Sobriety Date: January 2, 1987

Why she shared her story: “People have a very limited picture of what an alcoholic looks like, of what recovery looks like. Sharing as many different stories as possible is important. I came forward because we need to see all different kinds of recovery. We need to be more open about it.”

Lillian Henegar was 35 when she decided it was time to choose sobriety. She says she’s learned that many people are about that age when they decide to address their addiction. “That’s the age you start to see serious consequences,” she says. “That’s when I started waking up to what I could lose.”

Growing up in Bloomington in the 60s was just what many people imagine, says Lillian. “There were a lot of drugs,” the 64-year-old Bloomington Township Trustee recalls. “But for some reason, I chose not to use them. I know a lot of people’s stories start in adolescence, but mine doesn’t.”

Where her story starts is with an unhappy marriage at age 19 to a man several years her senior. “I got drunk one night on wine and it was like a revelation. I remember thinking, ‘I don’t know why everybody doesn’t do this!’ Fortunately, I didn’t have the money to do it all the time.”

Later, after she left her husband and continued her college education, things escalated. “I would go awhile and not get drunk and get things done. And then I would get drunk,” she says. “It turned out I was a binge drinker.”

By the time she was in her later 20s, she had a stable job and, when she was 28, she had a daughter. But her drinking continued. She says she was starting to feel ashamed of her behavior, but not enough to stop drinking.

“I remember doing things that, even if I wasn’t drunk when I did them, I can tie to being an alcoholic,” she says. “Like writing bad checks. That’s just one example of the things I did during this period that I’m ashamed of.” She says, too, that her drinking was becoming unpredictable. “I didn’t know where it was going to end. One glass or a bottle or more.”

Thanksgiving Day 1986 was a turning point. Lillian spent the holiday with her family and drank heavily all day. By the time dinner was over, she knew she wasn’t in any shape to drive home, and yet she did. “I didn’t want to ask for help, so I drove back in a quasi-blackout,” she says. “And I had my daughter, the most precious creature in the world to me, in the car.”

The drive shook her. “That was the wake-up. I couldn’t quite say I was an alcoholic, but I recall sitting on the couch in the dark and, even with all of this alcohol in my system, I was wide awake,” she says. “I remember thinking that normal people don’t drive drunk. Normal people don’t endanger their children’s lives.”

Not yet ready to admit she was addicted to alcohol, she spent the holiday season experimenting with what she calls controlled drinking. “I would go to events and have a drink or two,” she says. “And what I learned by doing that over and over was that it took so much effort for me not to have that third drink that it wasn’t worth it for me to have the first two.”

She also realized how freeing it was to not drink and to be able to drive home unimpaired. She saw how nice it was to wake up the next day and know exactly what she had done the night before.

On January 2, 1987, the family got together to celebrate Lillian’s sister’s birthday. When it came time for the champagne toast, she took a glass to raise it. “And then I thought, ‘I can’t do this,’” she says. “And after the toast, I didn’t even sip it, I just sat the glass down. That was it. That was my sobriety date.”

Looking back on more than 30 years of sobriety, Lillian remarks that living a sober life isn’t easy, and the community found in recovery support groups, meetings, and programs is invaluable. “We have to learn to manage ourselves and what life throws at us without using a mood-altering drug,” she says of those in recovery. “Yet, with each little change and small triumph, it gets easier and my self-confidence grows. I find I don’t miss alcohol at all. I have gratitude for all that my life has been and all that it has become.”

Steve Swihart.

Steve Swihart

Director, Bloomington Independent Restaurant Association

Sobriety Date: December 2, 2014

Why he shared his story: “We need to start a meaningful, public discussion erasing the stigma of addiction. It’s a treatable, complex condition of the brain—not a moral weakness. Nobody chooses to be an addict. People need to know there’s nonjudgmental help out there.”

Steve Swihart, 66, has lived in Bloomington since 1978. The Elkhart native has managed and owned several restaurants and is currently the director of the Bloomington Independent Restaurant Association (BIRA). A scientist by training, he’s worked as a microbiologist, a field geologist for a diamond exploration company, and a cytotechnologist doing microscopic cancer screening. He points all of this out for a reason: “Being an alcoholic doesn’t equate with being a failure,” he says. But, he adds, “If you have a problem, you need to take care of it or it will consume you.”

He knows what alcohol addiction can do to a person, a family, a career. “Dad was a prominent physician, and an avid drinker,” he says. “He couldn’t get help because he couldn’t let his patients know, though by the end he had lost his practice, his marriage, and his life. He died at 52 from a heart attack and a failed liver.”

While he did have an issue with drinking in college—“I thought I was going to be a doctor like my dad, but organic chemistry and alcohol told me I wasn’t. I flunked out.”—he rebounded, returned to school, and earned three degrees.

Married for 34 years to his wife, Theresa, who he says “has put up with an awful lot,” he never missed work, lost a job, or got into trouble with the law due to his drinking. In fact, he didn’t think he drank all that much.

“Over 30 or 40 years, I drank, on average, three or four beers a day, maybe a little more on weekends if I didn’t have anything else to do,” he says. “I did drink every day, however.”

He got a literal wake-up call when he had outpatient surgery in 2007. “I woke up tethered to the bed, and I’d been like that for two days,” he says. “The doctor said I was in alcohol withdrawal. I didn’t believe I could be alcohol dependent. But still, I’d been drinking every day for 40 years.”

He went through the detox process in the hospital, where he says he suffered from hallucinations and other physical withdrawal symptoms, and then checked himself into rehab. He was sober for three years.

“After a few months, I didn’t miss the routine of drinking,” he says of giving up beer. “Then, I was sitting on the beach in the Bahamas with my wife, and she ordered a glass of wine. And I said, ‘I’ll have one of those. It’s not beer. I can control my consumption.’ I drank for about a year before I realized I had a recurrent problem. All I had done was replace beer with wine. So I returned to rehab.”

Three years later, he poured a mixed drink. “It wasn’t even a conscious decision,” he says. “The quantity, just like with beer and wine, was progressive. I discovered the drug of choice in addiction is more. It didn’t take long. After about six weeks, I was waking up in the middle of the night just to have a drink so I could go back to sleep. At that point, I knew I was totally powerless over alcohol. I returned to rehab for a third time.”

He acknowledges that recovery is an ongoing process. “I will always be in recovery,” he says. “You have to be vigilant. I know that I can never be a social drinker again.”

Coming forward with his story means more people will know about his addiction—and that’s okay, he says. “My friends and family know, and I’ve told a few people I work with. I don’t wear a T-shirt that says, ‘I’m an alcoholic.’ But I’m no longer ashamed of it,” Steve says. “It’s not shameful to be an alcoholic. The shame comes when the consequences catch up with you—and they always will. I think people who know me respect me for what I do and who I am. Do I have regrets? Yes. But I believe I’m a good person who wants to do the right thing. Life is so much better in recovery.”

Elaine Guinn.

Elaine Guinn

Executive Director, New Hope for Families

Sobriety Date: June 3, 2016

Why she shared her story: “I wish everyone who struggles with addiction knew about trauma and understood about cumulative trauma. Then they wouldn’t feel shame. I wish we could look at addiction from a health perspective and not from a shame perspective.”

Elaine Guinn is the executive director of New Hope for Families, a nonprofit organization that offers shelter and resources to families facing homelessness. She talks to her clients about the trauma of their situations. The 46-year-old mother of two sons understands what her clients are going through—she was homeless twice as a child, and her family moved 15 times before she was 13 years old.

“Most of the time, when people think of trauma, they think of someone witnessing a murder or something on that scale,” she says. “What I realized was I was experiencing cumulative trauma throughout my childhood. It’s like an emotional earthquake each time you move. And my dad was an alcoholic. Every time Dad came home and his footsteps were unsteady, that could be a trauma, because it created uncertainty.”

She also talks to her clients about resilience. Her family first experienced homelessness when Elaine was 11, and she credits her mother for keeping their lives on an even keel. “I didn’t feel homeless,” she says. “I felt we were a family and we were in this together.”

The family—Elaine, her parents, and her older brother—lived in a pop-up camper for six months. “It was basically a tent on wheels” she says. “Mom would have us set the table—put out a tablecloth, count out the dishes—just like we did at home. The ritual was still there. It just felt like we were camping out.”

Over the years, her father’s drinking worsened. Her parents divorced when she was 19, and two years later her father was homeless.

“Through all of this, I would have occasions of heavy drinking that I thought of as normal,” Elaine says. “I did have warning signs in my 20s, glimpses of addiction. But I was so afraid of becoming that guy—becoming my dad, the homeless alcoholic. And I would use that as my measure.”

More recently, she says, she might spend months without drinking at all. “I didn’t even consider myself a drinker,” she says. Until she was.

“I was going through a health crisis a few years ago,” Elaine says, recollecting how she justified her drinking as a way to reduce stress. But her drinking escalated quickly. “It happened pretty fast—over a two-year period of time,” she says.

Several things had to happen before Elaine saw that she had a problem. “I remember my son saying, ‘Mom, you’re annoying when you drink,’” she recalls. “And I remember looking at my finances and thinking, ‘Where is all this money going?’

“The turning point came when I woke up with the worst hangover, and I realized who I am in this community and what it would mean for me to continue down this path,” she says. “The next day I reached out for help.”

Elaine says she feels lucky to have reached out when she did. “My dad lost it all,” she says. “I haven’t lost a thing. I have a house, my kids, my job. But I was starting to lose control of everything. It was just in the nick of time. I really believe if I had gone on one more day, I would have lost everything. And the work I do in this community is so important. Nothing is worth losing that.”

Elaine looks at her addiction through the lens of education, and that helps her understand it.

“Instead of looking at this situation and saying, ‘I’m a terrible person,’ I realized, ‘Of course this would happen to you. Of course you need to stay away from alcohol. Of course you need help. It just makes sense,’” she says. “And I don’t feel ashamed. I have information to help me not feel ashamed.”

Mike Long.

Mike Long

Owner, Long Leather Works

Sobriety Date: April 28, 2009

Why he shared his story: “If one person gets something out of this, it’s worth it. My hope is that this will have a ripple effect. If one guy can get some help, then his wife, his kids, other family members, as well as the people he works with will all be affected. One person getting sober, getting help, can change so many lives.”

Sitting in the Monroe County Jail, Mike Long had what he calls a “God moment”—a moment when he realized he wasn’t where he was supposed to be and he wasn’t doing what he needed to be doing.

Mike, who says he is “claustrophobic as hell,” was stuck in the drunk tank for the second time in a year. He was anxious and fidgety and, on top of that, the clock didn’t work, so he didn’t know how much longer he was going to be there.

“I remember looking through these little slats, trying to see the clock on the courthouse, when I saw my daughter drive by on the Square,” he recalls. “And I could see my granddaughter kicking her little legs in the backseat. And at that moment, I thought, ‘What the hell am I doing? I’m 56 years old and I’m in jail. I’m obviously making terrible decisions. And the root of my problem is drugs and alcohol.’”

Mike, now 65, didn’t know it then, but that day was a turning point. “That’s my sobriety day,” he says with pride. “And I celebrate my sobriety day more than I celebrate my belly button birthday.”

Mike’s story of addiction and recovery started when he was just 19. “I was in college and I had some roommates who were drug dealers, so I had access to a lot of drugs,” he says. “And I found out cocaine was amazing.”

By 21, he knew he was an addict. “I never sold drugs, I just arranged buyers. They didn’t pay me; I just had all the drugs I could use.”

It seemed like a downward spiral he might never escape. Luckily, Mike’s girlfriend got a job in Florida and asked him to go with her. “I was afraid to go, but I was afraid to stay here, too, because the drugs were getting to be a real problem,” he says. “So I went.”

In Florida, he cleaned up. The couple got married and had two children. Several years later, they moved back to Bloomington. “I was a teetotaler back then,” Mike says. “We would get a six-pack and it would last all week.”

Things changed as he got older. The self-employed owner of Long Leather Works ran into some old friends and picked up some old habits. “I’m not blaming the people I hung out with,” he says. “I chose my own path.”

After 11 years, his marriage dissolved. “My priorities had changed,” he says. “I went from being a devoted family man to wanting to do what I wanted to do.” A second marriage also ended in divorce. Happily remarried since November 2016, Mike says it was only after he got clean and sober that he could admit that drugs and alcohol had anything to do with the demise of his previous two marriages.

Mike was in jail for his God moment because he hadn’t followed the orders of his probation—no drugs or alcohol for six months. When he appeared for community service, he was given Breathalyzer and urine tests, which he failed.

After that second jail stay, Mike chose to follow his court-ordered instructions. He did his time on the road crew—sober. He worked through his Intensive Outpatient (IOP) program, even though he didn’t want to. “I realized it was good for me to go to IOP three nights a week,” he says.

Staying sober is an ongoing process, Mike says. “I’m still an addict. I’m still an alcoholic. I’m treated every day for my disease. And without treatment, I would go right back. Treatment for me is surrounding myself with people with similar problems, immersing myself in that community.

“I’m not proud of my past, but I’m proud that I’ve changed,” he says. “I don’t have anything to hide anymore.”

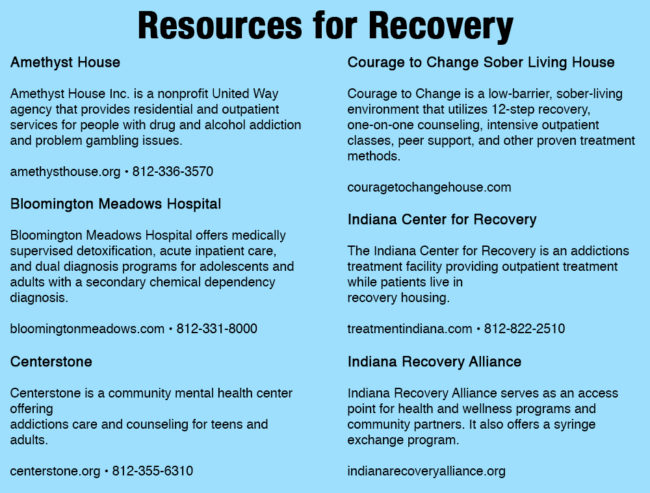

Resources for Recovery Quick-Links

Amethyst House • 812-336-3570

Bloomington Meadows Hospital • 812-331-8000

Centerstone • 812-355-6310

Courage to Change Sober Living House

Indiana Center for Recovery • 812-822-2510

Indiana Recovery Alliance

Inspirational stories.