‘A Code of Ethics Needed for Restaurants’

BY CARMEN SIERING

It’s easy to think of human trafficking as a horrible crime that impacts lives in far-flung places and is perpetuated by people different from ourselves. But the truth is human trafficking is a problem everywhere, and according to those who research the subject and work with its victims, we all need to ask more questions about the goods we buy, the services we use, and the restaurants where we dine. Toby Strout, executive director of Middle Way House, says she’s still haunted by a young woman who reached out to her for help a few years ago.

“I never got the whole story. She claimed to be 22, then admitted to 17,” Strout says. “I doubt she was that old. She worked at a local restaurant, lived with all the other workers. She never got any wages because her living expenses were taken out of her pay, like the old company towns in the 1800s. She had come into the country illegally, had no papers, and spoke no English.”

Strout says before any legal action could be taken, the girl disappeared, and the restaurant where the girl worked closed shortly thereafter. “I’m glad it’s gone,” she says. “But at the time people in the community went there a lot. I used to get invitations to events there. I would always decline to attend and suggested they investigate the labor practices of restaurants when making their choices.”

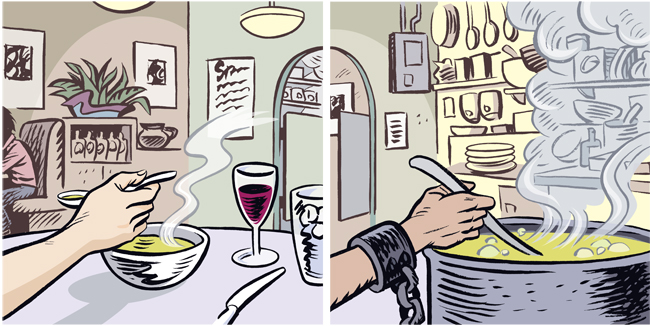

There is a growing awareness of labor practices many thought were outlawed and eliminated long ago. Stepanka Korytova is a researcher and adjunct professor who teaches courses on human trafficking at Indiana University. She says most people tend to focus on just one aspect of human trafficking — sex trafficking. “People get offended by the morality of sex trafficking, but we want cheap food, cheap clothes,” she says. “So we don’t think about the person who picked the tomato, or where our clothes were made. But it’s very possible the person who put in the labor was trafficked.”

Korytova also says we should consider what might be happening every time we eat out. “There are workers who are exploited behind the kitchen door,” she says. “It’s an illicit trade, so you can’t see it very clearly. But if you do see it, then you have to realize it’s just the tip of the iceberg.”

Stepanka Korytova researches human trafficking at IU. Photo by Shannon Zahnle

Recognizing and responding to human trafficking can be difficult. In October 2013, Deputy Attorney General Abigail Kuzma, along with members of the Indiana Protection for Abused and Trafficked Humans (IPATH) task force, were in Monroe County to provide training to those who might encounter human-trafficking victims. Participants included members of law enforcement, health care providers, educators, youth service providers, and victim advocates. The training was sponsored by the Monroe County Prosecutor’s Office.

“We want to be out in front of the problem,” says Monroe County Prosecutor Chris Gaal. “Based on statistics, there is probably a lot that isn’t recognized and isn’t reported in Monroe County. We wanted to train the first responders, and we anticipate reports will increase in the future.” While the training focused more on recognizing sex-trafficking victims, Gaal said his office is aware of the issue of labor trafficking and the need to be vigilant on that count. “We are concerned with labor trafficking as well,” he says. “We have had reports that it has occurred here. And certainly a lot of it goes on under the radar.”

As more people begin to recognize human trafficking and report it, the less likely it is to be an invisible problem, say Strout and Korytova. To that end, they suggest the city and county develop a code of ethics, written in such a way that workers and patrons of restaurants can understand it, to be posted in visible locations in area restaurants.

“There should be a sign that says, ‘These Are Your Rights’ in English, Spanish, Chinese, Russian — at least that many languages,” says Korytova. “And the workers should know they won’t be deported if they report their employer for abuses.”

They suggest that restaurants participating in the program receive a sticker or other symbol acknowledging their participation. “What I would expect to happen is there are so many restaurants that are absolutely aboveboard, no exploitation, and they would lead the way,” Korytova says. “The community would go to those restaurants, they would vote with their feet, and then the community as a whole would decide which restaurants would stay and which would go.”

Korytova says several groups — the Human Rights Commission, the Commission on the Status of Women, campus student groups — have been supportive of the code of ethics proposal. Now it is up to the city, The Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce, and the Bloomington Independent Restaurant Association to get behind the idea if it is to get off the ground.

“We just need someone to work with us on this,” Korytova says. “No one has said this is a bad idea, but no one has moved on it either.”