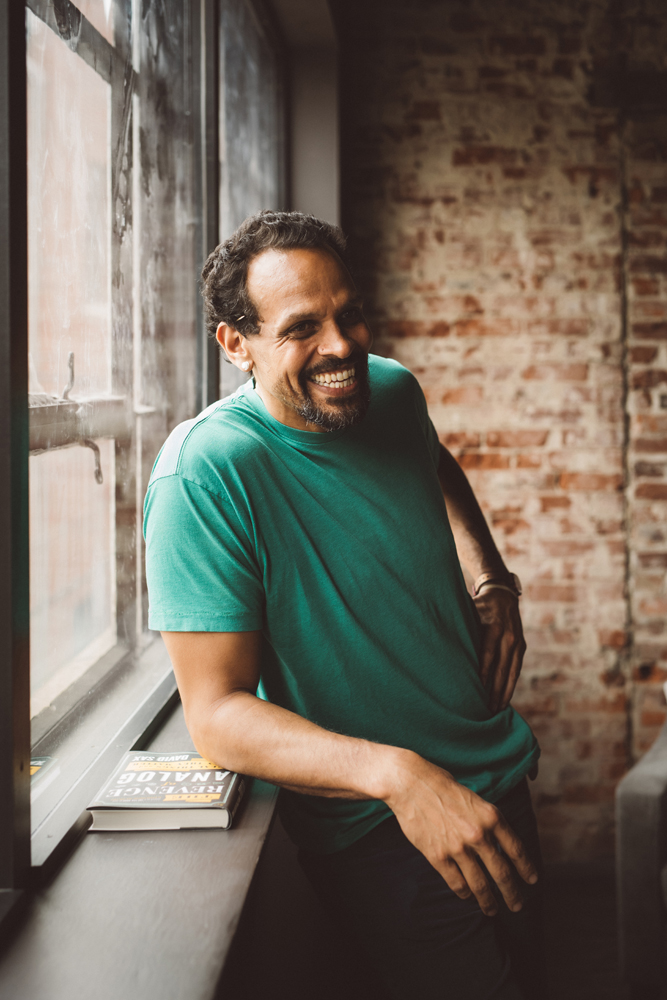

Scott Russell Sanders, (left) author and IU distinguished professor emeritus of English and writer of this story, shares a light moment with poets Catherine Bowman, Adrian Matejka, and Ross Gay.

BY SCOTT RUSSELL SANDERS

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEFF RICHARDSON

If you need a tonic to lift your spirits at this dismal time in our history, you should try poetry. It might even save your life. According to William Carlos Williams, a New Jersey doctor who scribbled lines of verse on the backs of prescription pads between visits from patients,

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

So what is found there? What vital nutrients for heart and spirit do poems provide? Bloomington, as it happens, is an excellent place to find out, for the city has been blessed with poets. Any given week, you might hear poetry readings at The Players Pub, Runcible Spoon, Ivy Tech John Waldron Arts Center, the Monroe County Public Library, the Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center, or other local gathering places. You might hear poetry broadcast on WFIU or WFHB. You might attend poetry slams, where competitors deliver their lines with the verve of Shakespearean actors or stand-up comedians. You might hear poetry declaimed from the courthouse steps in protest of injustice or war, hear it recited from a pulpit in service of a sermon, or hear it sung from a stage in a park as lyrics to a song.

Among Bloomington poets who have gained national acclaim, let me introduce you to three, all of whom teach in the Indiana University Department of English: Catherine Bowman, Adrian Matejka, and Ross Gay.

Catherine Bowman

“Strange things are always happening in the desert,” Bowman wrote in her first collection, 1-800-HOT-RIBS (Gibbs Smith, 1993; Carnegie Mellon Classic Contemporary Series, 2000), winner of the Peregrine Smith Poetry Prize and the Kate Tufts Discovery award. The landscape she had in mind in 1-800-HOT-RIBS is the border region of Mexico and Texas, near her birthplace in El Paso. “I remember wandering among the Pecos River ravines, the Rio Grande arroyos, the cactus, the rattlers, tumbling with the tumbleweeds, and marveling at the stars at night over the desert.”

Having grown up along such porous borders, she relishes what she calls “threshold spaces,” zones of mystery and uncertainty. “I love ambiguity in poetry, where we can simultaneously experience light and darkness, feel both comforted and uneasy, find the ordinary in the extraordinary,” she says. “For me, poetry is a kind of shape-shifting or trickstering.” Bowman’s blue eyes carry a trickster’s gleam, and her poems shine with astonishment at the quirks of people and the powers of nature.

As the oldest of three children, and the only girl, she spent a lot of time in childhood exploring the land by herself, collecting stones, feathers, flowers, and nests to make what she calls “natural altars.” “Many of my poems are like that,” she explains. “Made from pieces of memory and language I’ve gathered—a kind of offering.” 1-800-HOT-RIBS and her second book, Rock Farm (1996), draw on those early experiences and on family history from both sides of the border, including poems about a great-grandmother’s refusal to dance with Pancho Villa, a grandfather’s work as a metallurgist in the silver mines of the Sierra Madres, and a grandmother’s pickled watermelon rind jelly. Bowman says, “For me, poems are a kind of preserve, like a pickle full of salty brine and sweet spice.”

At the age of 8, she was given a copy of Louis Untermeyer’s Golden Treasury of Poetry, and she spent countless hours reading and memorizing the poems—from nursery rhymes and fables to Poe’s “Annabel Lee” and Shakespeare’s Mab, queen of the fairies. She also loved the folk, rock, and country-western songs her father sang to her. Hymns and the Bible were other early influences. “Maybe that’s why so many of my poems are a retelling of the Garden of Eden story,” she says.

Bowman began making poems without imagining she would grow up to become a poet, the way another child might draw pictures without aspiring to become an artist. Family and friends would ask her to read her poems, and she gladly obliged. “As I grew older, my spirit always drew me back to poetry” she recalls.

In college at The University of Texas at San Antonio, while majoring in political science, she was praised for her poems by teachers in two creative writing classes. After graduation, she earned a living freelancing for newspapers and magazines in San Antonio, teaching English in Spain, working on a cruise ship as a blackjack dealer, and waiting tables. Finally, at age 27, she gave in to her calling and enrolled in Columbia University’s M.F.A. program to immerse herself in writing. In the evenings, she went to poetry readings, where she heard a wide range of styles and voices, and where she developed a keen appreciation for poetry as an oral art form.

Several years later, feeling that radio listeners should have a chance to hear this marvelous array of voices, Bowman suggested to the producers of NPR’s All Things Considered that they include a segment on poetry, as “another way of telling the news.” To support her pitch, she recorded a demo cassette of five poets reading their work at her kitchen table. The producers embraced the idea, and invited her not merely to recruit the poets but also to host the readings on-air. And so, for most of a decade beginning in 1995, Bowman served as NPR’s “poetry DJ,” introducing dozens of writers to audiences worldwide. Her selection of poems featured on the program was published in a volume called Word of Mouth (Vintage, 2003).

An invitation to serve as a visiting writer at Indiana University drew her to Bloomington in 1996. She prospered in the classroom and on the page, and in due time became a tenured full professor. “My aim through writing and teaching,” she says, “is to create meeting places for conversations between the poem and the reader, between personal and public experiences.”

The years Bowman spent in New York City inspired her third collection, Notarikon (Four Way, 2006), which offers an homage to the city, to food, and to jazz, and reflects on a 10-year marriage ending in divorce. Her research in the archive of poet Sylvia Plath in the IU Lilly Library led her to write The Plath Cabinet (Four Way, 2009), which includes poems about Plath’s hair, paper dolls, wedding invitations, passports, and diaries.

In addition to delving into archives, Bowman has collaborated with filmmakers, composers, musicians, and artists to produce sound pieces, videos, and visual art. Among those collaborators is her mother, Tita Bowman, whose artwork appears in Rock Farm. In 2015, 16 of Bowman’s poems were etched on outdoor mirrors as part of installations by the artist Mary Miss to foster awareness of the precious and endangered waterways of Indianapolis. “Working with ecologists on this project,” she says, “I learned how essential it is to protect and nurture our riparian habitats, that diverse area between land and stream. I think it’s just as essential to nurture and protect our own riparian imagination and consciousness.”

“All around us the underground world overflows with love,” Bowman writes in her most recent book, Can I Finish, Please? (2016). She is speaking here of trees, whose roots mingle and share nutrients companionably, but she might as well be speaking about her own way of treating other creatures, including those on the 40 acres outside of Bloomington where she moved several years ago. “I think of my farm as a wildlife sanctuary,” she says, “a place for horses, turtles, birds, and frogs.” This place also gave rise to many of the new poems, in which tools offer advice on love, a walking stick guides the poet through haunted stone quarries, an antlered deer dwells inside a locket, and people transform into horses. From the wild fringes of her land, she gathers flowers to distill their essences, as she gathers moments and images from the wild fringes of her life to make poems. “Po-eems” is how she pronounces the word, a lovely stretching of the diphthong common in speech from her part of Texas.

“Poetry for me is about stirring things up, troubling the waters—but it’s also a way of getting me out of trouble, a kind of solace,” Bowman says. “A poem is a lens for seeing things that might otherwise be invisible, a container for what might otherwise be lost.”

Don’t we all need such rescues from trouble, such containers for treasures?

Adrian Matejka

Among the troubles at the heart of Adrian Matejka’s poetry is the dilemma of being “mixed”—combining in his body and mind qualities that defy the fictional divisions of “race.” The genes that merged to shape him flowed through a Euro-American mother, an African American father, and, on his father’s side, a Delaware Indian grandmother. The result is a man whose features would well represent our nation in a gallery of the world’s peoples. We’d be bragging if we put Matejka on a poster to symbolize today’s America, but right now we could benefit from showing a dignified, intelligent face to other nations.

His parents met in Los Angeles, then moved to Germany, where his father was stationed as a GI between tours in Vietnam, and his mother worked as a U.N. translator. So it happened that Matejka was born in Nuremburg and spoke German as his first language. Now he speaks it only in occasional dreams. By the time his family moved from Germany to Indianapolis, where he passed through the double gauntlet of adolescence and poverty, he had lost not only his first language but also his father:

While marriage was difficult, the divorce

was simple. Dad packed, Mom watched.

Dad got the records, Mom got the kids:

three afroed half-and-halfs with no idea

of the goings on.

Those lines appear in Matejka’s first collection of poems, The Devil’s Garden (Alice James Books, 2003), where he describes himself as a “half-blood.” “Whatever group I’m with, they tend to see me as Other,” he says. “A lot of white Americans think I’m Mexican; Mexicans think I’m from the Middle East.” In Mixology (Penguin Books, 2009), his second book, he quotes director Spike Lee as telling him, “You ain’t even black.”

“Bad to be black,” Matejka writes, “worse to be a mixed indetermination.” Aside from violating the illusory distinctions of race, however, mixing is often an enrichment, as the poems in Mixology suggest, with their celebration of mulatto artists, hybrid musical forms, polyglot street slang, and pop fusion. In his pages, such blending appears as the driving force of culture, as it is of biology.

Living in an apartment on the east side of Indianapolis until his mother remarried, Matejka and his siblings experienced “the hungry days before payday” and the “powerlessness of not having.” When there was no money for the electric bill, the lights went out. A second marriage carried the family to the city’s west side, into

one of the smaller

Indiana suburbs where there aren’t

supposed to be black folks.

Having a stepdad couldn’t relieve Matejka from his “black father’s absent jurisdiction,” which showed in his “city of skin.” This absence led to what Matejka calls his “daddy fixation.”

“I keep asking, how do you learn to be a man if there aren’t any men around?” In search of role models, he was drawn to innovative black artists—the comedian Richard Pryor, the painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, and musicians such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Sun Ra, and Prince.

His third poetry collection, The Big Smoke (Penguin Books, 2013), focused on a different sort of black artist—Jack Johnson, the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion. Despite his prowess in the ring, Johnson was eventually jailed for dating white women. After burning through his prize money, the champ appears in the book’s final poem as a man nearing 60, wearing a “dog-eared blue suit,” taking questions from a flea-circus crowd. This account of a black man’s heroic rise and tragic fall, told mostly in Johnson’s voice, was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award.

What inspired The Big Smoke? “My mother was a big boxing fan. We’d watch it on TV,” Matejka says. “Everywhere we went, she’d check out the local boxing scene. Later, I discovered she was betting on the fights. And when the guy she was backing lost, she’d say, ‘He’s no Jack Johnson.’ So I wanted to find out who Jack Johnson was.”

Matejka has the physique of a middleweight boxer, but his prime sport is basketball, which he learned on the courts of Indianapolis as a youth:

In Indiana, you either play

ball or deal with abjection

everywhere like a rocket ship

crashed into the moon’s eye.

The story of that youth is told vividly in his latest collection, Map to the Stars (Penguin Books, 2017). Coming of age during the Reagan era, he dreamed of becoming an astronaut, yearning for

those intergalactic

Star Wars spaces

without races.

“In school, we always watched the shuttle launches,” he says. “They conveyed a sense of patriotism that transcended race. There were even black astronauts.”

In college at IU, his dream of exploring outer space gave way to a dream of exploring inner space through writing. The turning point came one evening at Runcible Spoon, where the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Yusef Komunyakaa, then a faculty member at IU, gave a benefit reading. Listening spellbound to Komunyakaa, Matejka decided, “I want to do what he does!”

Matejka spent those years at IU completing majors in English and psychology and coming one course shy of a major in African American Studies. He left Bloomington after graduating in 1995, then returned in 2012 to join the faculty of his alma mater. His art matured during those intervening years. “I was a rapper with a band when I was an undergrad,” he recalls, then adds with a laugh, “I was terrible, but I learned how to carry myself on stage.”

He’s on stage a lot these days, giving readings coast to coast. He has delivered the Jack Johnson poems in three boxing arenas—an upscale one in Miami; a funky one in Cleveland; and, most recently, a Golden Gloves venue in Indianapolis. Closer to home, since winning the regional Indiana Authors Award in 2015, he has traveled all over the state with support from Indiana Humanities, presenting his writing in places that may never have hosted a poet before.

At present, taking a break from poetry, he is collaborating with a French illustrator on a graphic novel. “It’s new for me,” he says, “but I learn by trying things outside my comfort zone.” He’s also writing essays, including one about advising his 11-year-old daughter, Marley, “on what to do if she’s pulled over by cops.” Marley is bound to love language, for Matejka’s wife, Stacey Lynn Brown, is also a poet, and a faculty member in the IU Department of English.

“I’m grateful to be where I am, doing what I’m doing,” Matejka says. “I’ve received so many gifts from my teachers, from editors and literary judges, from my colleagues.” Reflecting on those colleagues, he adds: “Cathy [Bowman] and Ross [Gay]—those two are Poets with a capital ‘p.’ They reach out to communities beyond the academy, spreading the power of poetry.”

Ross Gay

Gratitude runs like a bright thread through the work of Ross Gay. His first collection, Against Which (CavanKerry, 2006), concludes with a poem entitled “Thank You,” and those two words also form the last line in the book. The same sentiment echoes through his most recent collection, Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015), especially in the powerful title poem:

and thank you the way my father one time came back in a dream

by plucking the two cables beneath my chin

like a bass fiddle’s strings

and played me until I woke singing,

no kidding, singing, smiling,

thank you, thank you.

His father had died from liver cancer, and could return only in memory or dream. So the gratitude Gay expresses, here and throughout his poetry, arises in spite of grief and loss.

“With so many awful things happening, we can fail to notice the goodness,” he says. “Cruelty and pain aren’t the only truths about our lives. I want to talk about what I love, too.”

In his second collection, Bringing the Shovel Down (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011), he broods about lynchings, bullets, bombs, and the “mind’s roaring machinery,” yet he also rejoices over blessings, large and small:

there are, on this planet alone, something like two

million naturally occurring sweet things …

But look; my niece is running through a field

calling my name. My neighbor sings like

an angel

and at the end of my block is a basketball court.

Even without benefit of a Hoosier upbringing, Gay shares Matejka’s love of hoops. He’s built like a football tight end—the position he played in high school and at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania—but basketball is his favored sport. He coached it during his early years of teaching near Philadelphia, where he grew up—and up. Everything about him is big—his height, wingspan, imagination, appetite, his laugh that makes dishes clatter in the cupboard, his smile that could light up a cave.

“As a kid, I was into sports and skateboarding,” he recalls. “I also loved drawing and painting, and I was crazy about music. Not much of a reader, though. One time I was listening to an Earth, Wind & Fire record, studying the lyrics, and I heard my dad say to my mom, ‘Well, at least he’s reading something.’” Gay was turned on to books during his sophomore year at Lafayette College, when a teacher introduced him to the work of the African American writer Amiri Baraka. “That lit my fire,” he says. “I couldn’t get enough of Baraka, or poetry, or books. I read everything I could get my hands on.”

Today, Gay’s own books are in the hands of readers across the country, especially Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award. It also won the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, which honors a poet in mid-career.

These distinctions, added to a recent Guggenheim Fellowship, have not altered Gay’s wardrobe, which features T-shirts, jeans, and running shoes. This garb allows him to move easily between writing poems and digging in the dirt. The backyard of his white frame house in Bloomington’s Prospect Hill neighborhood harbors a compost heap, berry bushes, and raised beds, which are luxuriant in summer with enough veggies to support his vegan cuisine. In a nearby lot, the fruit trees he planted soon after moving to town in 2008 bear peaches, plums, and pears.

Those and dozens of other fruits and berries are now weighing down trees and bushes at the Bloomington Community Orchard, which Gay and other generous souls began planting on city land in 2010. “Folks who heard about it kept asking, ‘Who gets the fruit?’” Gay says, laughing. “We never thought about who gets the fruit. Our whole idea was to share the earth’s abundance. We wanted to practice being good neighbors. We’re in this life together.”

He’s currently at work on This Black Earth, a prose book about his relationship to the land. He traces his love of growing things to childhood visits with his mother’s family, farmers in Minnesota. He’s also at work on a collection of poems spun from a famous moment in professional basketball—a gravity-defying move by Philadelphia 76ers’ star Julius Erving, known as Dr. J., who lifted the modern game to new heights above the rim.

Bloomington is obviously a prime place for a poet who’s crazy about basketball. How else has living here affected his writing? “Every which way,” he says. “The orchard, neighbors, friends I’ve made, my students, the weather—it’s all in my poetry. I could have rooted myself someplace else, but I’ve made a home here.” Indeed, Gay has invested himself in the community to a degree rare among writers, who tend to avoid whatever might interfere with their work.

Why does he write? “To become clearer to myself,” he says. “It’s a spiritual practice, I guess. I’m trying to cultivate my humanity by understanding myself and others more deeply.” Among those he has come to understand is his father. “He and I butted heads a lot when I was growing up,” he acknowledges. “But over the years, especially after he got cancer, our struggle faded. The older I got, the more I recognized our common human frailty, and the more I understood my dad.”

Gay describes another of his current writing projects, The Book of Delights, as “an adult reflection on joy, in face of the knowledge that everything we love will eventually perish.” This poet of loss and praise, of grief and growth, knows in his bones the truth of that outlandish claim by William Carlos Williams—that poetry may save our lives. If you’re skeptical, read a book by Bowman or Matejka or Gay, and if you get a chance to hear any of them perform their work, by all means go. What you hear, what you read, will be news that matters.

Since a poet ought to have the final word, listen to these lines from Gay:

Here’s what I think I’m trying to say:

Somewhere there’s a road.

Some of us are going to find it.

You can come if you want.

For samples of our poets’ work and an exclusive photo gallery of their interview with Scott Russell Sanders, see below.

CHARLIE PARKER BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION, TOMPKINS SQUARE PARK

by Catherine Bowman

I was telling you about that junkie wannabe

from Wall Street who ODed last week

on Explosion 2000 on that street corner

right over there when KABOOM! you kissed me

smack on the lips just as “Confirmation” kicked in.

Just as Venus in two-toned dreadlocks and a skin-tight

smock danced from the band shell with her pet python,

Bodyguard, to “All the Things You Are.”

Just as punk rockers rocked, in-flowered on sheets,

sipped smoothies and smoked,

their hair spirited to pastel auras, rosehip,

island lime, a shade of blue just washed by rain.

Just as Ukrainians checkmated, as twins seesawed,

as bikers cracked smiles in the Hari-Hari, the slap-

tongue of sax. All the mommies and the poppies. Just as.

And they were doing the brothers in descending order.

The three brothers Heath: Percy, Jimmy, call him “Little Bird,”

and Albert “Tootie” Heath. With Milt Jackson on vibes,

three score and twelve, and still working. Two boys in love

grooved, one in white pants and a sailor hat,

the other in a buffalo nickel belt that bedazzled.

They sat on the park bench eating falafel.

A man with one leg sold charms for a dollar. For luck.

For the music that day and the light, you could say it was all

bell-bottomed and swaybacked. Young-like.

And your kiss. All at once I was riding a sparkling gold Schwinn bike.

Something in my head went from full torpor to starburst:

as if whetted by some wild vibrato, your kiss,

the vibes’ licks cleared my vision of fizz for an instant.

What had been all Midnight Dragon was now

a Tropicana-Pure-Premium-sharpened C

delivered as of this morning to the Santa Barbara Deli

and Superetti down the street. Just like that.

In your arms and the music and the light, I thought I might

go plumb or Pentecostal, lay down on the grass, recite

Kahlil, take up knitting, eat pickles and marry you–

Tell that priest to stop playing Frisbee with the lab

so we can say our vows right here and now before “Tenor Madness”

ends! Oops! I forgot we’re already married! Just as.

Gymopédies No. 1

by Adrian Matejka

That was the week

it didn’t stop snowing.

That was the week

five-fingered trees fell

on houses & power lines

broke like somebody waiting

for payday in a snowstorm.

That snow week, my daughter

& I trudged over the broken branches

fidgeting through the snow

like hungry fingers through

an empty pocket.

Over the termite-hollowed stump

as squat as a flat tire.

Over the hollow

the fox dives into

when we open the back door at night.

That was the week of snow

& it glittered like every

Christmas card we could

remember while my daughter

poked around for the best place

to stand a snowman. One

with a pinecone nose.

One with thumb-pressed

eyes to see the whole

picture once things warm up.