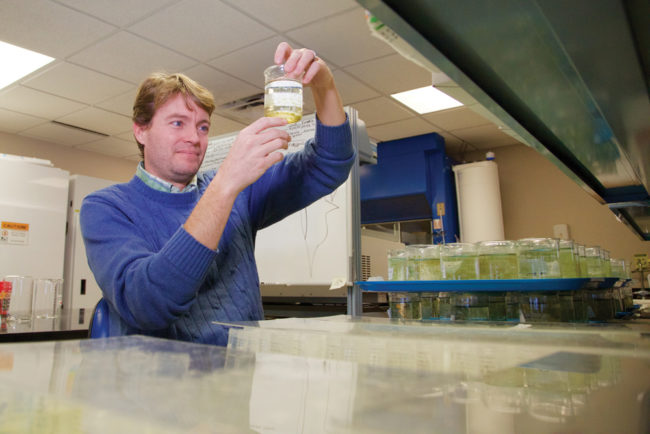

Stephen “Chip” Glaholt at work in the lab. Photo by Jim Krause

BY SUSAN M. BRACKNEY

Where others see waste, Stephen “Chip” Glaholt and Mark Menefee see opportunity. Co-leaders on the new Indiana University photobioreactor project, Glaholt and Menefee plan to put photosynthetic

algae to work high atop IU’s Central Heating Plant. There, carbon- and nitrogen-rich emissions will be condensed and diverted from plant smokestacks to a maze of algae-filled pipes. Add a little sunlight and the waste is transformed into nutrient-rich biofertilizer.

Mark Menefee. Photo by Jim Krause

The algae slated for the photobioreactor is a non-GMO variety from Glaholt’s lab. “It doesn’t have the ability to create toxins,” says Glaholt, an adjunct professor and researcher with the IU School of Public and Environmental Affairs. “It’s a very safe algae that’s found in the Midwest.”

The fertilizer, which contains quick-release liquids that give plants an immediate boost and slow-release solids that feed them long-term, will be applied on grass and ornamentals campus-wide—potentially saving the university $4,000 annually in fertilizer costs. What’s more, the photobioreactor is expected to sequester 200 pounds of carbon during the summer months alone.

A beaker of photosynthetic algae. Photo by Jim Krause

“The reason using flue gases from the Central Heating Plant works so well is that we’re burning 95 percent natural gas,” says Menefee, Central Heating Plant assistant director for utility services. “The flue gases have 10 percent carbon dioxide content. This very concentrated carbon dioxide feeds the algae.”

Although flue gases will naturally aerate the algae, a pump will also be used to promote circulation. Small Styrofoam cylinders floating within the algae-waste mixture will gently scrape and clean the insides of the pipes, allowing sunlight to penetrate and photosynthesis to continue.

Funded with a $50,000 Duke Energy grant, the photobioreactor should be operational this spring and, once established, will also serve as a living laboratory, affording students opportunities to study and monitor it. “I have an experiment that just finished to manipulate the NPK [nitrogen-phosphorous-potassium] ratio of our algae,” Glaholt says. “We’re doing that with undergrads. So, if you want orchid fertilizer or lawn fertilizer or tree fertilizer with different NPK ratios, we should be able to do that.” Undergrads will also regularly harvest the fertilizer.

As for using biofertilizer on food crops? “The USDA has too many hoops to jump through for that,” Glaholt explains. But, he notes, there are other applications. “We can make dried algae pellets for animal food,” he says. “Tilapia would love to eat algae pellets that we can make organically. The future really is wide open.”