Spring is upon us, and with it comes new life in the form of fragrant flowers and greenery, and the bugs that depend on them. As part of Bloom’s Greatest Hits, take a look at this feature story from our June/July 2013 issue honoring the bugs of Bloomington and the important roles they play.

The robber fly–”These are the combat helicopters of the insect world.” Photo by Darryl Smith

BY ADAM KENT-ISAAC | PHOTOGRAPHY BY DARRYL SMITH

Bugs. They are everywhere, especially in summer. Regarded as an annoyance by most humans and scary by some, their lives often culminate in an unceremonious finale: splattered on a windshield, squished under a boot, poisoned by insecticides, whacked with a rolled-up newspaper, or eaten.

It’s not an easy life. And while some bugs, such as bloodthirsty mosquitoes and ruinous termites, arguably deserve such fates, even good bugs get little respect.

That’s probably because bugs are so small and we know so little about them. But in their own buggy world, they build structures, compete for resources, and form complex societies. And, when viewed close up, their faces show as much character as, well, some people.

Bloomington photographer Darryl Smith turned his lens on the local bug population to give us a closer look. And Armin Moczek, Ph.D., of Indiana University’s department of biology and an expert on insect evolution, offered his insights into what makes bugs tick.

Note: The insects and spiders are identified here by the most specific taxonomic group that Moczek was able to discern from the photographs, with “species” being the most specific, followed by “genus” and “family.”

Bald-faced hornet (species: Dolichovespula maculata)

The bald-faced hornet–”If you do bother them, they will make you pay.” Photo by Darryl Smith

Bald-faced hornets, which are related to yellow jackets, are “a really important pest controller,” according to Moczek. “If you’re worried about caterpillars eating your garden, you want these guys around. They’re great.”

These hornets are typically found high up in trees, so the probability of interacting with them is minimal. They are unlikely to target humans unless their nest is disturbed. But, Moczek warns, “If you do bother them, they will make you pay.”

Bald-faced hornets build annual nests using regurgitated materials. “If you find a nest that’s been in your attic for a few years, there’s nobody home,” says Moczek. “It’s not like they’ll come out of it every year. Once they’ve left the nest, there’s no reason to destroy it. Bring it to me and I will preserve it, because it’s a work of art.”

Cuckoo wasp (family: Chrysididae)

The cuckoo wasp–”It’s a brutal process, officially termed ‘kleptoparasitism.'” Photo by Darryl Smith

Some wasps hijack the bodies of other insects using grisly methods that the most gruesome serial killers would be hard pressed to outdo. The cuckoo wasp is one such creature. A small, solitary wasp with vivid colors, it is fairly widespread, and in its adult form, it feeds on the nectar of flowers.

All well and good, but when the cuckoo wasp is ready to lay its eggs, explains Moczek, it will parasitize the nest of another insect, such as the cicada killer wasp, itself a brazen parasite.

“Cicada killer wasps will dig a tunnel and fill it with the body of a paralyzed cicada, and lay an egg on it,” says Moczek. “The cuckoo wasp will go in and lay an egg on top of that egg, which will hatch first, killing the original egg, and then the larva will feed off of the cicada. Or it will wait until the original egg hatches and develops, and then parasitize it.” It’s a brutal process, officially termed “kleptoparasitism,” and illustrates the lengths to which some species will go to perpetuate their offspring.

Bee (family: Apidae)

The honeybee. Photo by Darryl Smith

“There are bazillions of different kinds of bees out there,” says Moczek, who was not able to pin down exactly what sort is depicted in the photograph feeding on the nectar of a flower. “But it looks sufficiently close to a honeybee that it might well be one.”

Honeybees do sting, and, as with all stinging wasps and bees, it’s the females that do the deed; in fact, the stinger is part of the same organ that is used to lay eggs. Males cannot sting. While solitary female wasps, such as the cuckoo wasp, and bees can both sting and lay eggs, says Moczek, among the social honeybees only the queen can do both. Worker bees do not lay eggs, and they use their stinger solely for defense.

The honeybee mechanism of stinging also differs from other stinging bees and wasps. “When a yellow jacket or a hornet stings you,” says Moczek, “they can sting again and again and again. Each time they sting, they inject a little venom and leave behind a little pheromone that marks you as the enemy, so the other ones can smell you.”

Honeybees, on the other hand, are one-and-done. “When they sting, the stinger has a little barb that catches inside your tissue and then gets ripped out of the bee’s body and stays in you,” explains Moczek. “It’s not only the stinger that stays in you but the whole venom gland, the muscle that squeezes it, and the nerve that enervates the muscle. This whole chunk of stuff gets ripped out of her abdomen and stays in you and keeps pumping venom. The honeybee kills herself in the process. About two hours later, she’ll be dead from massive internal injury.”

Skipper (family: Hesperioidea)

The skipper–”They are the macho men of the butterfly world.” Photo by Darryl Smith

Is it a butterfly or a moth? “Well, it actually is a bit more complicated than that,” explains Moczek. “The organisms that we colloquially call butterflies are really a special group of moths. A close relative to these ‘true’ butterflies is the skipper. It lacks the bright colors typically associated with butterflies, but like true butterflies it is active during the day and has short, club-shaped antennae.”

The macho men of the butterfly world, “skippers are very hairy and have strong upper bodies,” says Moczek. “Nothing flimsy about these guys.” Their powerful wings enable them to swiftly dart from flower to flower, hence their name. They are important pollinators.

Spined micrathena spider (species: Micrathena gracilis)

The spined micrathena spider–”The spiky armor may be a form of mimicry.” Photo by Darryl Smith

Spiders may be bugs, but they are not insects. Instead, they belong to a separate group, the arachnids. There are many fundamental differences between spiders and insects. For example, spiders have two major body regions and insects have three. Also, spiders have eight legs and insects have six. And among bugs, only insects ever evolved wings and the ability to fly. Spiders, at best, can glide.

The most noticeable feature of this minuscule web-building spider is its bulbous abdomen, technically called the opisthosoma, covered in spiny protrusions, the purpose of which, Moczek admits, is not fully understood. He says the spiky armor may be a form of mimicry or camouflage. “If you have to defend yourself but you don’t have a nasty bite or venom, there are two ways: Look scary or look like something else.”

An insect’s or spider’s form of mimicry depends on the predators that feed on it. To our eyes, he says, the spined micrathena spider’s mimicry may not work because the spikes make it stand out only more. “But to a bird, it might be helpful [in disguising the spider].”

Dogbane leaf beetle (family: Chrysomelidae)

The dogbane leaf beetle–”The beetle is not actually blue.” Photo by Darryl Smith

“I’ve seen these by the hundreds in Bryan Park,” Moczek says of the brilliantly colored leaf beetle. The one in the picture is a dogbane leaf beetle, which feeds on the dogbane plant, although there are more than 35,000 specialized varieties in the family. They are common in a wide variety of habitats. Some of the most destructive garden pests, such as the Colorado potato beetle, are in this family, but the dogbane leaf beetle specifically is not a threat to anyone’s garden.

The iridescent coloring, says Moczek, is caused by a phenomenon known as interference. “The beetle’s cuticle is not actually covered by blue or purple pigment; instead, its surface is shaped in such a way that colors of different wavelengths bounce off of it and interfere with each other in such a way that all that is reflected is the color you see,” he says. “If you alter the surface, like by putting a drop of liquid on it, the color changes.”

Flesh fly (family: Sarcophagidae)

The flesh fly–”The moment something has died … these guys are there.” Photo by Darryl Smith

Bugs of the type shown in the photograph are commonly called “flesh flies.” The moment something has died and becomes carrion, “these guys are there,” says Moczek, noting that they are important to the field of forensics for this very reason. “They will initially colonize natural openings in the body. If there’s a wound, that’s where they will go, and they will reproduce like crazy. Because they are such reliable arrivers, you can date back the time of death of a body based on their developmental stages.”

Larval insect development is very much context-dependent on humidity and especially temperature. Modern forensics investigators can consult tables, developed over the past few decades, to determine time of death based on the type, and especially age, of larval insects found on the body.

Robber Fly (family: Asilidae)

The robber fly–”Its head is basically all eyes.” Photo by Darryl Smith

“These are the combat helicopters of the insect world,” says Moczek. Robber flies are aerial predators, swooping down on other insects in flight and grabbing them for a meal. “They’re incredibly accurate visual predators, and some of them engage in bee mimicry—they look fuzzy, like bumblebees, so that they are protected from birds. Its head is basically all eyes; it depends so much on vision. This makes sense. If you’re a predator, you only get one shot. And if you miss, there goes your meal.” *

A mind-boggling world

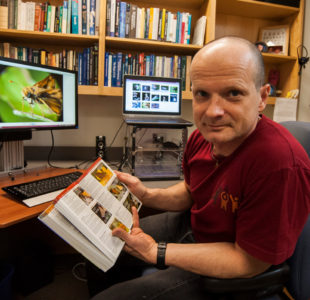

Armin Moczek of Indiana University’s department of biology, an expert on insect evolution. Photo by Adam Kent-Isaac

“There are aspects to insect social life that are out of this world,” says Moczek. “The lengths to which parasites go to take advantage of their hosts, and what ends hosts go to outmaneuver their parasites, is mind-boggling. And the cool thing about it is, we’re accustomed to thinking that you have to go to weird, exotic places to find this kind of life. But this is all right here. You just have to take the time to learn about it.”

To learn more:

• IU students can enroll in Moczek’s insect biology class, which is an intense lecture/ lab course with only minimal prerequisites.

• The National Audubon Society’s regional chapter, the Sassafras Audobon Society, which serves Monroe, Brown, and several other counties, focuses on birds but also includes the study of insects, particularly butterflies.

• WonderLab science museum often presents insect-related exhibits and demonstrations. Moczek himself frequently works with WonderLab, and with local and regional teachers, to provide educational programs about insects.

A note about the photographer

To take the bug photographs, IU photojournalism student Darryl Smith taped together two small, inexpensive manual-focus lenses for his Pentax single-lens reflex camera. By doing so, he increased the focal length, enabling a super-magnified view, which is focused simply by its proximity to the subject. An external hand-held flash was used to freeze the action and illuminate the details. Click here to visit his photography Facebook page.