by PETER DORFMAN

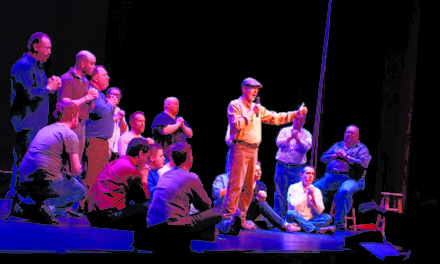

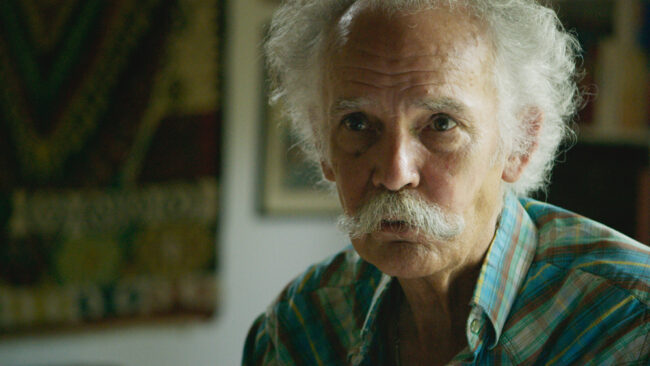

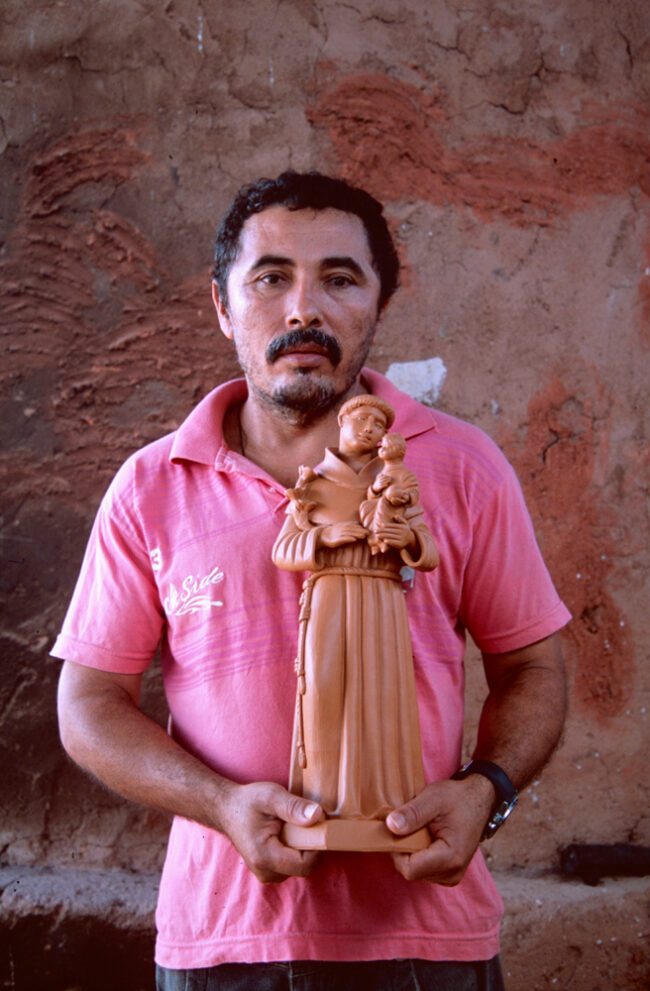

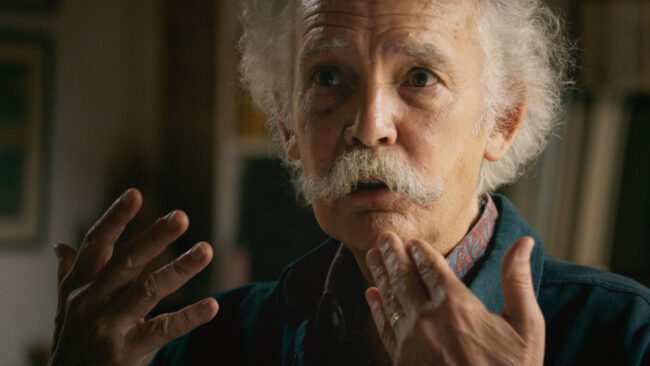

The documentary film Henry Glassie: Field Work opens with a series of vignettes of Brazilian sculptors creating traditional sacred art. Not until 30 minutes into the film does Glassie, an internationally renowned folklorist and Indiana University professor emeritus, make an appearance.

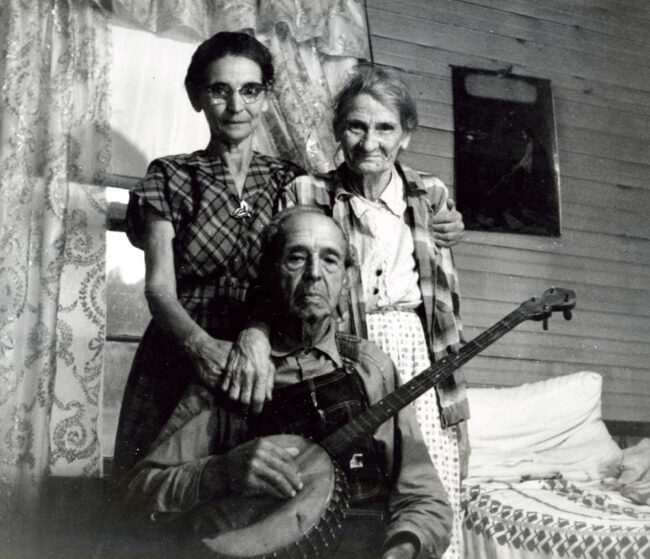

By cinematic standards, the pacing is languid, intended to evoke the artist’s immersion in his work. Irish filmmaker Pat Collins captures the patient observation that is a hallmark of Glassie’s approach to field work, which just happens to be his signature contribution to the folklorist’s science. In Ireland, Turkey, Nigeria, Brazil, and other places, Glassie has quietly and appreciatively blended into the artists’ communities he’s studied, committing as much as a decade to each project.

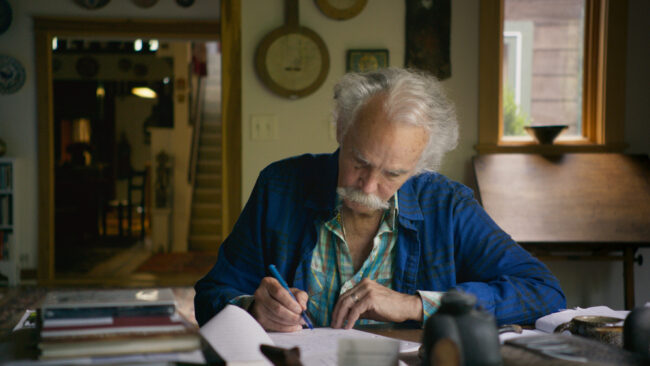

Collins became interested in Glassie’s work when he heard him interviewed on Irish radio. “He liked what I’d said about the nature of community and individual creativity,” Glassie recalls.

Glassie wasn’t immediately interested in being the subject of a film. But he was interested in capturing the working process of the artists he was studying. “I offered Pat a deal,” he says. “He could do a film on me if he would follow us in Brazil and get us good footage of our Brazilian artists.”

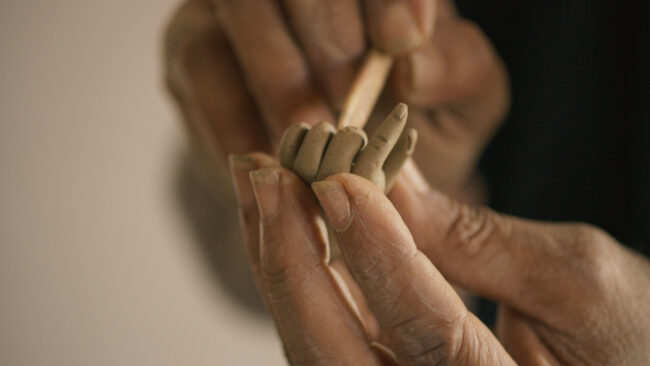

The subject of the film, and of Glassie’s field work, is the individual artist making art. Glassie is less interested in the end product than in the process of creation, which frequently is difficult and time-consuming to record authentically.

“If you show up with a camera, people will perform,” he says. “But I didn’t want to record a performance.”

After recording the Brazilian field work, Collins took his crew to North Carolina, where Glassie was working with local potters Daniel and Kate Johnston. Collins added

a section on Glassie’s work in Turkey, using footage shot by another filmmaker.

Glassie says he’s interested in the individual will of the creative person under uncontrollable conditions. “A woman on a mountainside in Turkey weaves beautiful carpets,” he explains. “She does that in an environment that makes agriculture really difficult, but where you can raise sheep. That’s a condition that leads to her making magnificent art.”

He makes a point of doing as much of his work as possible in the native language of the people he studies. His Turkish is fluent. His Portuguese is less so, but his wife, folklorist and IU professor Pravina Shukla, grew up in Brazil and has interpreted during his field work there.

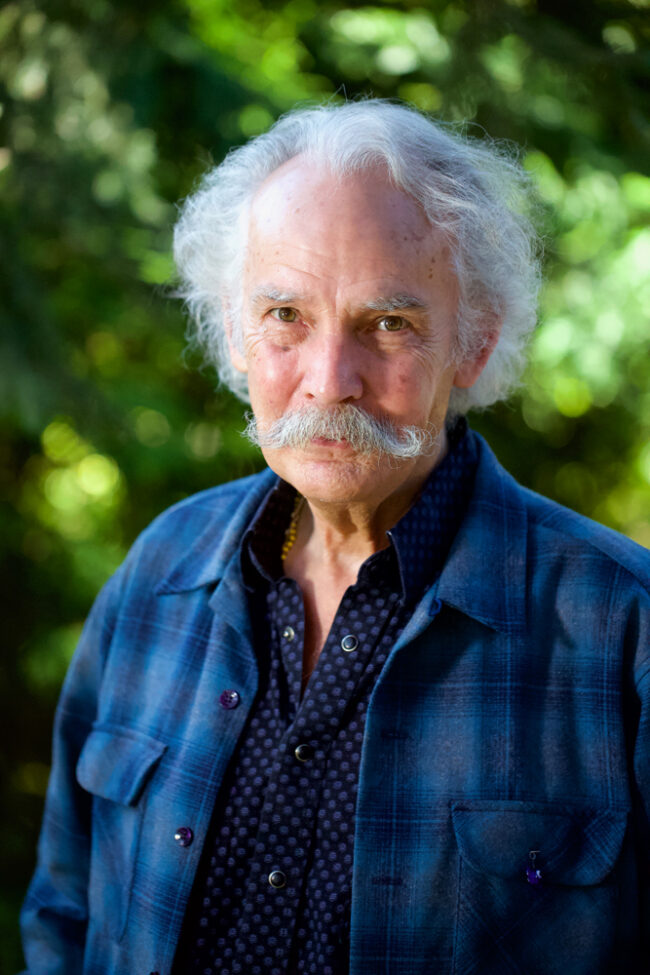

Glassie, 78, came to Bloomington in 1970 to take a position at the Indiana University Folklore Institute. “IU has the oldest folklore department in the United States, maybe the best in the world,” he says. “I got my Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania, the other really good department, but as a young folklorist, IU was where you wanted to teach.” Glassie taught at IU for 43 years.

A topic he has returned to often is the vernacular architecture of the American South. He has written and spoken frequently on Bloomington’s vernacular architecture, which he characterizes as distinctly Southern—small houses in rows, with small yards around them, in a melting pot of immigrant styles and techniques brought north from Kentucky and Tennessee to Bloomington, where it essentially stops. “You really don’t see the characteristic Bloomington styles north of here,” he notes.

A strong proponent of historic preservation, Glassie is a past president and board member of Bloomington Restorations Inc., a nonprofit which he calls the only successful developer of affordable housing in Bloomington. “BRI has put a lot of houses in the hands of people who don’t have money, he says. “If you refurbish old houses, all the money stays in town. These big apartment blocks appearing around the city don’t benefit Bloomington’s economy at all.”

Glassie advocates restoring or building small houses on small lots throughout the city using local resources instead of outsourcing the growth of the city’s housing stock to out-of-town developers. “The best thing you can do, environmentally or socially, is repair old buildings, not demolish them to build new ones,” he argues.

Henry Glassie: Field Work premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2019. Bloomington audiences can see it at the IU Cinema in April.

To view the trailer, visit tiff.net/events/henry-glassie-field-work.

See a gallery of photos from the documentary below.

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

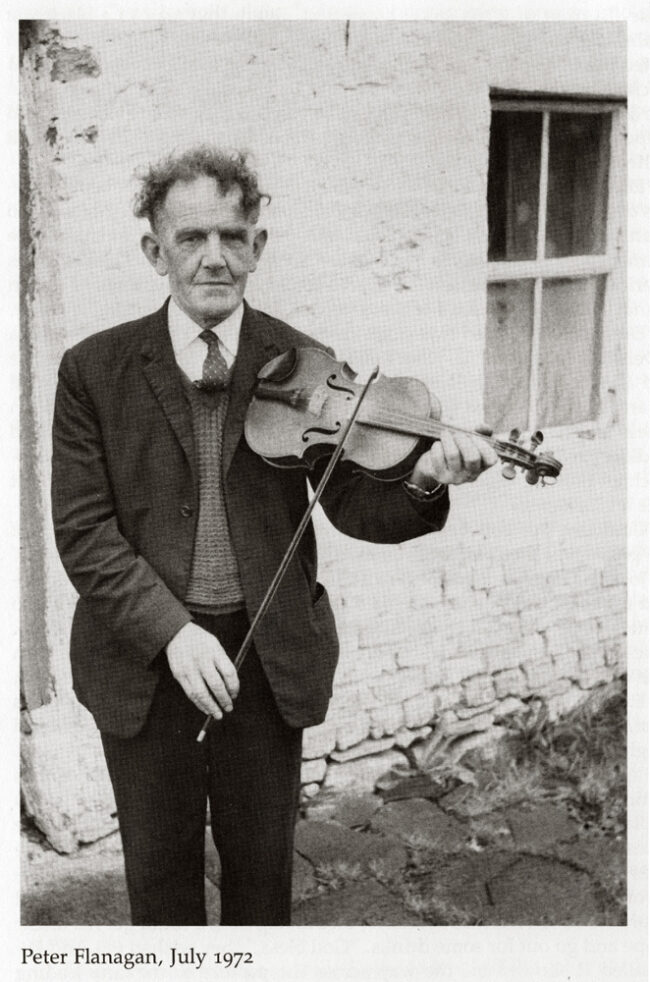

Peter Flanagan, one of the Irish musicians profiled in Glassie’s The Stars of Ballymenone. Courtesy Photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo

Courtesy photo