BY JULIE GRAY

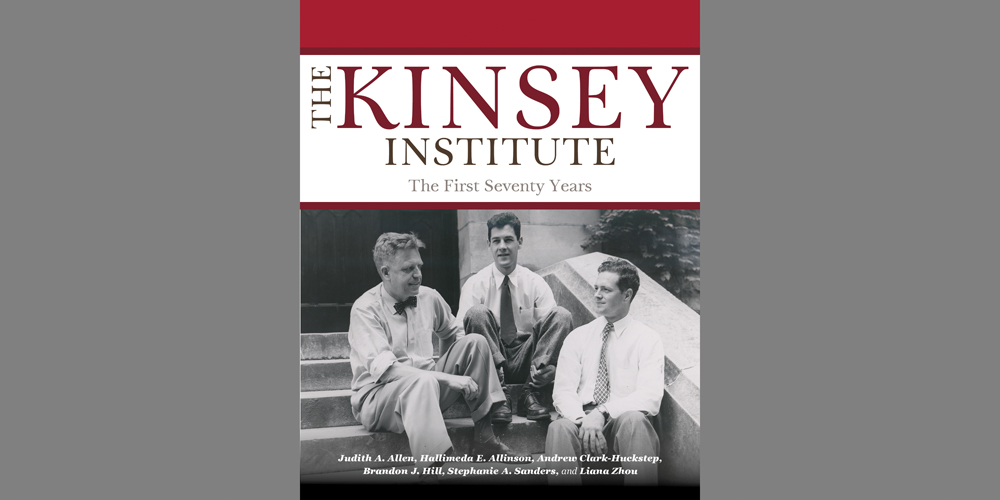

The six scholars who wrote The Kinsey Institute: The First Seventy Years knew they were running risks. Their subject had already been extensively covered, not only in academic studies but in films like the 2004 biopic Kinsey. And they feared that their affiliations with the Institute would lead their book to be dismissed as a mere “in-house infomercial.”

Yet they felt that there were still areas, such as the Institute’s activities after Alfred Kinsey’s death, that remained unexplored. So they plunged in. The result is a loving examination rather than a critical exposé. By the conclusion, the authors abandon any pretense at impartiality, writing, “Even with uncertainties and unsolved problems, the seventieth anniversary of the Institute is an occasion for joy.”

That joy is well-merited—the Institute’s survival has never been assured, having been under nearly constant attack on ideological grounds, beginning with Cold War McCarthyites crying that Kinsey’s research undermined the American family and paved the way for Communism. In the 1950s, the U.S. Customs Service tried to seize materials bound for the Institute’s library on grounds that they were obscene. In the 1980s and 1990s, evangelicals and American conservatives resurrected old attacks on the Institute’s research and ethics. Over and over, both national and state legislators have tried to defund the Institute.

In the face of such attacks, some institutions, such as The Rockefeller Foundation, were cowed and withdrew their support. Nevertheless, the Kinsey Institute carried on, not only thanks to its researchers and staff, but also thanks to the administration and trustees of Indiana University.

IU’s support was good not just for the Kinsey Institute—it also made IU “preeminent among American universities for defending academic freedom.” Such a defense is all the more important today as the executive branch of the national government mounts a concerted attack on science. People with no scientific credentials are being nominated for important posts such as NASA administrator, and scientists are being purged from agency advisory committees.

The authors of the Kinsey history could not have known that their book would serve as a timely reminder of the importance of academic freedom, though they do mention the Nazis’ chilling campaigns against sexology and psychoanalysis. But given recent events, their history acquires added importance as the poignant and surprising tale of how a scientist who started his career as an expert on gall wasps succeeded at establishing an institute with worldwide impact and renown.