by SUSAN M. BRACKNEY

Linda Smith’s research subjects may be pint-size, but the data they’re providing is vast.

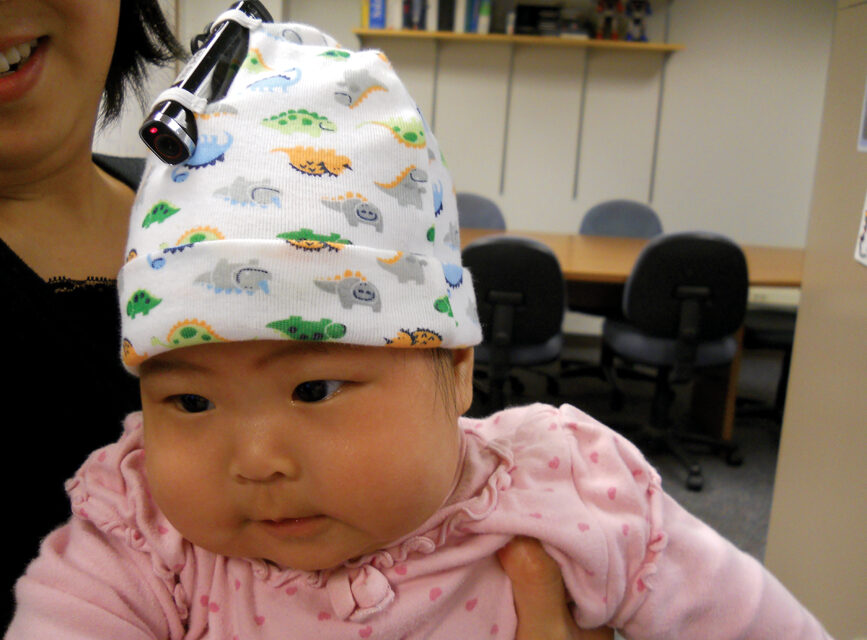

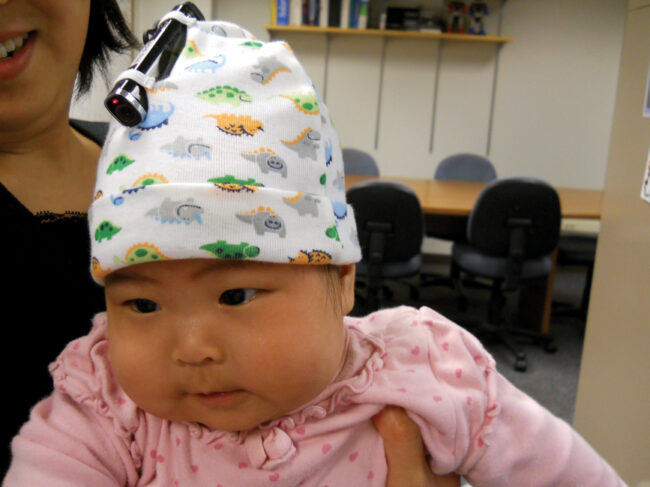

“When we [Smith and her collaborator, associate professor of cognitive science Chen Yu] bring a baby in here and they play and they have a head-mounted eye tracker and motion sensors on, they’re all recording at 30 frames per second,” the Indiana University distinguished and chancellor’s professor of psychological and brain sciences says. “We have data from the right hand, the left hand, the head, data from where the eyes are, data from what the images are in front of them as they move their body and walk around the room. It’s very dense data.”

Smith has been with IU since 1977 and was recently named to the National Academy of Sciences. She specializes in early child development. Of particular interest to her is determining how children learn their first object names—considered to be the entry point for language since these provide a base for learning other word types like adjectives and verbs.

“How are we going to understand any one of our systems—vision, language, problem-solving, social skills—if we don’t know how it gets made over time?” Smith asks. “[We need to] know the processes by which we go from little babies into having the full-fledged social skills, cognitive abilities, or language abilities that we have as adults.”

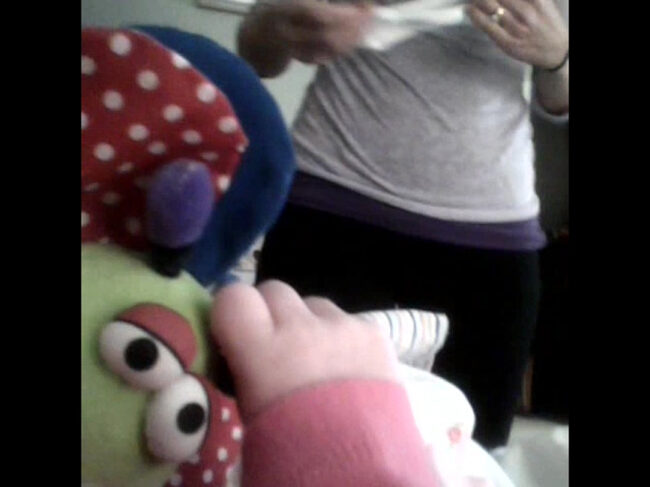

Smith says that babies at play focus intently on just one object at a time. “Objects in the baby’s view tend to look very large,” she says. “Even when they’re not holding an object, they’ll lean forward so the thing they’re looking at is almost the only thing in view.”

Of course, gathering these kinds of insights only works when the babies’ head-mounted eye tracker and motion sensors stay put.

About 80% of the time, all goes well. “Younger toddlers are better—9-, 12-, 14-month-olds—you get it on and, as long as it doesn’t move, they’ll forget about it and just carry on,” Smith explains. “Two-year-olds are pretty good, too, because you can explain to them, ‘This is our special hat, and you need to wear it.’” What about 18-month-olds? “They’re the worst,” Smith admits. “They’re more autonomous than the little guys, and they don’t forget they’re wearing something.”

Thanks to Smith’s collaborators, Yu and and David Crandall, associate professor of informatics and computing, as well as students at the IU Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering, some of the data she’s collected is being analyzed with data science and machine-learning techniques. “Our goal is to not even have to look at the images ourselves,” Smith says. “We can ask for what the visual properties of the image are—the amount of clutter, lighting conditions, figure-ground issues.”

Still, there is only so much a computer can do. “We can’t ask for content,” Smith explains. “There’s nothing good enough to tell us ‘There’s a cup in view’ or ‘The baby’s stirring oatmeal in a bowl.’ That we still have to do with people.” Ironically, improving artificial intelligence tools is one potential application for her research findings. Babies, it seems, are the cutting edge of AI.

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos

Images captured by 12- to 16-month-old research subjects in the IU project. Courtesy photos