by CARMEN SIERING

photography by MARTIN BOLING

In January 1984, during the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII between the Los Angeles Raiders and the Washington Redskins, Apple launched its famous “1984” television commercial, introducing the world to the Apple Macintosh personal computer.

The ad, filmed in gray tones, features expressionless humans walking into an assembly where a Big Brother figure harangues them on a large screen. Interspersed with these images is one of a woman in a white T-shirt and bright red shorts—the only spot of color— being chased by storm troopers. As she enters the assembly, she throws a sledgehammer at the screen. The resulting explosion releases a blast of fresh air, and a voiceover reads: “On January 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’”

The commercial, and the tagline, were a direct reference to George Orwell’s dystopian novel, and offered reassurance to viewers that personal computing technology—at that time new and possibly intimidating—was nothing to fear.

It must have worked. According to a 2014 Business Insider 30th anniversary retrospective, the Ridley Scott–directed commercial had consumers “mesmerized by its state-of-the art cinematography and alluring message about the promise of technology.” So mesmerized, in fact, that $155 million worth of Macintosh computers were sold in the three months following the Super Bowl.

Looking back, 1984 was a pivotal year in personal computing. And, as it happens, that year was also crucial for women in the field of computer science.

Personal computers were used primarily to play games and were marketed almost exclusively to boys.

A New York Times article entitled “The Secret History of Women in Coding” notes, “If we want to pinpoint a moment when women began to be forced out of programming, we can look at one year: 1984. A decade earlier, a study revealed that the numbers of men and women who expressed an interest in coding as a career were equal.” The article goes on to note that by the 1983-84 academic year, 37.1% of all students graduating with degrees in computer and information sciences were women. But, from 1984 onward the percentage dropped, and by 2010, it had been cut in half—only 17.6% of students in those same programs were women.

The irony? Researchers believe it was the rise of personal computers—thought by many to be a democratizing technology— that led to the decline of women in the field. Personal computers were used primarily to play games and were marketed almost exclusively to boys.

First, the bad news

Laurie Burns McRobbie, adjunct professor in the Indiana University Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering and IU’s first lady, says she saw the trend first-hand. A Michigan native, McRobbie started her IT career working with Merit Network, a nonprofit research and education network governed by Michigan’s public universities.

“I started in about 1983,” McRobbie says. “That happened to be the high point for women getting computer science degrees. And it’s just gone down ever since. That shift happened when the personal computer came out, and the rise of the gaming culture.”

McRobbie says that while she left IT in 2007, she’s remained interested in the field and why women are underrepresented. “There’s research that speaks to it,” she says. “A lot of it comes from [researcher] Jane Margolis from Carnegie Mellon University. She really looked at what they could do to address the gender gap and boost the number of women in their programs.”

Margolis partnered with researcher Allan Fisher to explore how societal biases and other barriers influence women’s choices to pursue careers in computer science. Among their findings was the suggestion that women are more interested in the social applications of how computers can be used, such as to make a positive impact on their communities, on people’s lives, or to solve an immediate problem. Men, on the other hand, are more interested in programming, which includes, but is not limited to, coding and creating software.

Other important reasons women are unrepresented include the fact that many male students come to college with prior programming experience, not to mention a built-in peer group of like-minded computer friends.

A 2016 University of Washington study reiterates Margolis and Fisher’s findings. Researchers found three factors

most likely to explain gendered patterns in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields—a lack of pre-college experience, gender gaps in women’s beliefs about their own abilities, and a male-dominated culture that discourages women from participating.

“Women are drawn to do something that allows them to apply what they are learning in the classroom.” –Laurie Burns McRobbie

Diana Nixon is a computer scientist and former associate professor and assistant chair of information technology at Ivy Tech Community College–Bloomington. “When I took my first course in computer science and learned [programming language] FORTRAN in the summer of 1985, I had no sense that I was any less prepared than any of my peers,” Nixon says. “Now, one of the things that routinely happens at the collegiate level is students are very aware that other students have coded before. There is more of a range of experience coming into college courses, and every computer science department has to deal with that in one way or another.”

At Carnegie Mellon, these issues were addressed head-on by deemphasizing prior programming experience (the feeling was that coding could be taught) and by providing female students with mentors and networking opportunities. The outcome?

In 1995, at the beginning of the study, the entering enrollment of women in the undergraduate computer science program at Carnegie Mellon was 8%. By 2015 that number had grown to 40%, nearly three times the national average. Additionally, women in the computer science program were earning degrees at a percentage comparable to their male counterparts.

McRobbie wanted to explore how the issue might be addressed at IU.

“I’ve done studies and I’m aware that women aren’t treated equally. … I’ve heard women talk about it as a thousand paper cuts.” –Maureen Biggers

“I had looked at their research,” McRobbie says. “When I talked to Kirsten Grønbjerg [distinguished professor, O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs], she asked if I had thought about doing a clinic, something like a law school clinic. And, according to the research, that would be a lot more appealing to young women, and it might draw more of them into computing and informatics.”

In 2010, Serve IT, a service-learning course that students take as a for-credit internship through the Luddy School, was founded by McRobbie and Maureen Biggers, executive director and co-founder (along with McRobbie) of the Center of Excellence for Women & Technology (CEW&T). Students in Serve IT are placed on teams and assigned to area nonprofit organizations where they help with information technology needs.

Serve IT has done what the two hoped it would do, McRobbie says. “It’s gratifying to see the demographics of the clinic beating the demographics of the school as whole,” she says. “Women are drawn to do something that allows them to apply what they are learning in the classroom.”

Not that the Luddy School is not drawing women to its programs. Biggers says that since she arrived here in 2008, the number of women in the school has quadrupled. But, she says, there are still problems.

“I’ve done studies and I’m aware that women aren’t treated equally,” she says. “It affects interest, it affects retention, it affects who is studying STEM. And I think a lot of girls don’t even know it’s happening, but it is, and it does affect them. I’ve heard women talk about it as a thousand paper cuts.”

The place to start isn’t college. Biggers says the work needs to start much earlier. “How can we work with teachers to have them promote equitable and inclusive environments?” she asks. “It’s a cultural thing, but the more people are aware of it, the more that can be done about it.”

Monroe County schools take the lead

At the state level, Indiana is poised to begin addressing a lack of computer science education. With the passage of Senate Enrolled Act 172, schools must incorporate computer science in grades K-8 and offer it as an elective for grades 9-12. The bill includes funding for computer science teacher training. Only 222 of 525 Indiana high schools offered at least one computer science course in the 2016-17 school year, according to the Indiana Department of Education.

But the Monroe County Community School Corporation (MCCSC) has already begun addressing the need for more computer science education. According to Anne Leftwich, associate professor of instructional systems technology at IU, MCCSC is working well above state computer science standards. In fact, in some ways, it may be setting the standard.

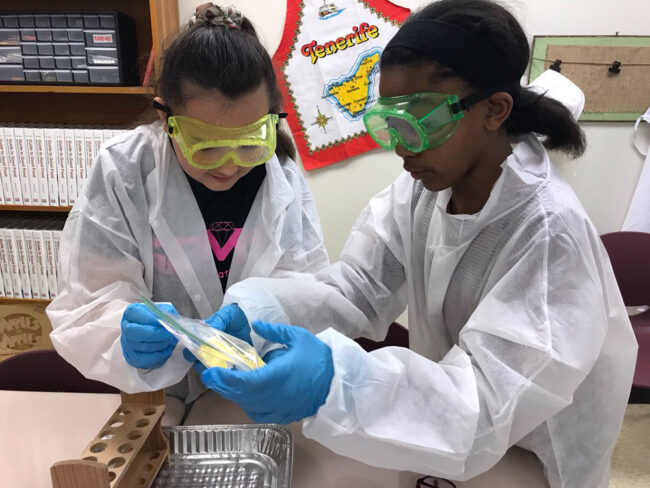

Students in the STEM lab at Grandview Elementary School.

“We want every kid—girls and boys—at every grade level, to have consistent access to computer science, to STEM, all of that.” –Markay Winston

Dr. Markay Winston, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction, and Katy Sparks, the district-wide STEM and computer science coach, are behind a relatively new, robust STEM curriculum at MCCSC that gives teachers approachable, actionable lessons to teach each quarter.

“In large part due to Sparks and Winston, MCCSC has put together a cohesive plan and is being asked for that plan [by other school corporations],” says Leftwich, who is also a facilitator for code.org, a nonprofit dedicated to expanding computer science access to schools and increasing participation by women and underrepresented minorities.

“We want every kid—girls and boys at every grade level—to have consistent access to computer science, to STEM, all of that,” Winston says. “And teachers have been very responsive and receptive that every kid will have the same computer science education pre-K through grade 6.”

In the classroom, STEM coaches provide one-on-one technology assistance with both hardware and software. The 2018-19 academic year was the first to implement a K-6 computer science curriculum that included digital citizenship, coding, a STEM challenge, and productive technology. The middle school science curriculum is being piloted this year. Educators hope there is a “trickle up” effect going forward, especially when it comes to getting more girls interested in STEM classes in high school.

“I think that is going to go a long way to changing enrollments in high school computer science classes,” says Seth Pizzo, a computer science teacher at Bloomington High School South. “But there’s more that can be done.” Pizzo mentions colleagues across the country who have redecorated classrooms to be more appealing to female students, and a teacher in Florida who goes to girls’ sports teams, asking them to sign up for his computer science classes as a group.

“I’m more focused on the idea that if I do a good job teaching my courses, more students will sign up—the ‘If you build it, they will come’ philosophy,’” Pizzo says with a laugh. “I try not to cater toward boys or girls but make it all very neutral.”

But when asked how many girls are in his computer science classes, Pizzo admits the numbers are rather dismal. “It fluctuates from year to year,” he says. “But generally speaking? It’s about 10 to 20%.”

The girls’ club

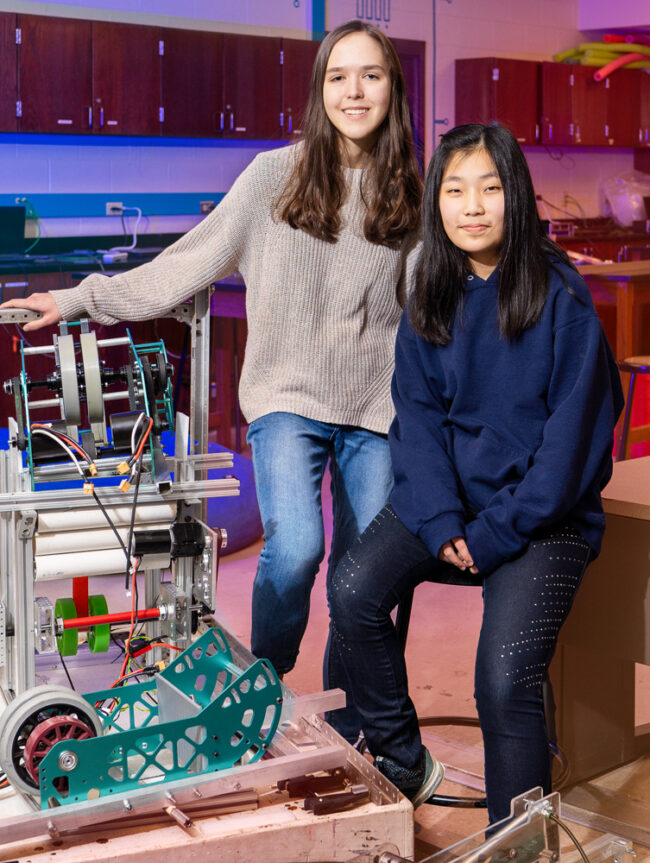

Two girls who have taken Pizzo’s class are juniors Elenna Kim and Katrina Brown. They’re part of South’s Girls Who Code Club; Pizzo is the group’s sponsor. Kim started the club three years ago. Even in high school, the young women are aware of the gender gap in STEM classes and occupations.

(l-r) Katrina Brown and Elenna Kim.

“I knew there were a lot fewer girls [in computer science classes],” Kim says about starting the club. “So I thought if

we could create a friendly environment, it would encourage them and engage them and maybe they would take a computer science class later.”

For Brown, the idea of being a single-gender group has its own appeal. “Most females are aware of the gender divide in STEM, so they’re afraid to ask questions because they are reinforcing that stereotype,” she says. “It’s easier to ask questions at Girls Who Code, and therefore grow and become a better programmer.”

And that leads back to the Carnegie Mellon research that intrigued McRobbie—research that pointed to male students’ prior coding experience as they entered college and female students who, for the most part, didn’t have much or any prior coding experience.

Brown, who is involved in the robotics club at South, has already taken an intro to computer programming course and has signed up for a course on artificial intelligence at IU. “I’m a programmer,” she says without hesitation. “I think I’ll continue robotics. And machine learning is an interesting topic.”

The fact that Kim and Brown are sticking with computer science in high school is significant. Many, if not most, girls lose interest in STEM subjects, particularly computer science, in middle school.

“We do a great job getting girls into computers,” says Nathan Ensmenger, chair of informatics at the IU Luddy School. “The key moment seems to be about eighth grade. But we also see it at the university level when women drop out [of computer science programs]. And then again when women graduate with computer science degrees and then leave the industry for other white- collar occupations.”

Danise Alano-Martin is product owner for Envisage Technologies and board president of Huminetrix, a Bloomington-based technology nonprofit. She says she never doubted her own ability to study science (she minored in environmental studies) or work in IT because she had a terrific role model—her mother, Nancy Mitchell.

“My mom’s first job in computer programming was in the late ’70s,” Alano-Martin says. “She worked for a bank in account management. Later she worked at Crane [Naval Surface Warfare Center] implementing software at different naval ports and bases. I did that for Envisage until I became the product owner. It took me a month or two before I realized I was doing the same job my mom used to do.”

Women leading the way

Melissa Blunck is the director of the Women in STEM Living-Learning Center (LLC) at IU, a community of about 50 undergraduate women who live together in

Danise Alano-Martin.

Wells Quad on East 3rd Street, all of whom have a STEM major or interest. The LLC offers programming, academic development opportunities, community building, and career development, Blunck says.

“First-year students can talk to older students about scheduling, navigating IU systems, and classes,” Blunck says. “We have opportunities for them to meet with current grad students and medical students where they can eat a meal with them, talk to them about grad school or medical school and find out what it is actually like, not what they might hear from a faculty member.”

Nineteen-year-old IU sophomores Gracie Baker, a biotechnology major, and Emma Wiesler, a microbiology major, have both lived in the Women in STEM LLC for two years. Both say the LLC has allowed them to develop friendships and support systems they might not have found otherwise. Outside the LLC, they have noticed some differences between men and women in their STEM classes.

“I’ve noticed that the men in my classes feel more comfortable speaking out and they do take over class a bit,” Baker says.

Wiesler concurs, adding, “The thing I’ve noticed is that the men in class are the ones who are asking questions and getting clarification on what they don’t understand. Though I haven’t noticed male professors treating anyone differently, which is good.”

Both young women are in the biological sciences, which are among the most equitable of the STEM fields. According to the National Science Foundation (NSF), women held the majority of degrees at every level in the biological sciences in 2016. Other fields are not as equitable. The NSF notes that in the physical sciences broadly, women earned fewer than half of the degrees awarded. In chemistry, that number was highest, at 45% of bachelor’s degrees and 39% of master’s and doctoral degrees.

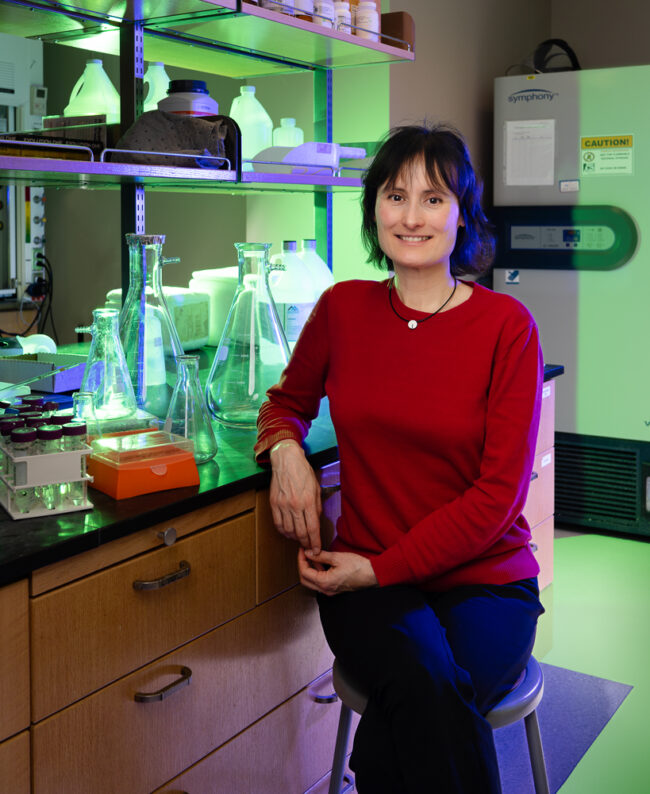

Nicola Pohl is a professor and the Joan & Marvin Carmack Chair in the IU Department of Chemistry. She came to IU in 2012 as a senior faculty member.

“You don’t see loads of photographs of women running their labs.” –Nicola Pohl

“We’ve had a very slow increase in the number of women faculty,” she says. “It was really, really bad. So, we’re up to 15% female faculty in my department. When they hired me, they also hired two [female] junior faculty and doubled the number of women in our department.”

Nicola Pohl.

Pohl says that while the number of women in her field has been increasing, they still face other issues.

“The problem I see is there is not much societal pressure for women to use their skills and their education,” she says. She does see a way to encourage them, however. As a faculty member, she says, she can influence how women see themselves.

“I can be explicit in what I see in terms of talent,” Pohl says. “I can say, ‘I see you having my job someday.’ Sometimes it’s hard to envision that. It’s basically little nudges along the way that allow us to envision ourselves as PhDs, as scientists. Especially when society doesn’t do that. You don’t see loads of photographs of women running their labs.”

Giving women those helpful nudges can happen outside the classroom and the lab, too. Pohl is the STEM faculty affiliates director for the Center of Excellence for Women & Technology (CEW&T), the program founded by Maureen Biggers and Laurie Burns McRobbie. Women helping other women become more comfortable with technology in a space that is, for the most part, occupied by women, can be very empowering. CEW&T is reaching across disciplines, encouraging more women to join the group.

“One of the things we did recently was change our name,” Biggers says. The organization used to focus on women “in” technology. Now it focuses on women “and” technology. “We created this group for all students, for all faculty, staff, and alums.”

And for men, too, albeit in a very specific role. Male Allies and Advocates for Equity offers men the opportunity to promote and support the center’s efforts to develop gender equity at IU. Through workshops, the male allies group learns about the challenges women in technological fields face and how to use that knowledge to raise awareness.

Nathan Ensmenger.

Ensmenger, the Luddy School informatics chair, has participated in the male allies group. “There are things

you can learn,” he says. “As chair of the department, I’ve tried to intervene more publicly. I think one of the more disheartening things for our female students is if these things just keep happening. Maybe that’s the most powerful role a male advocate can have—I’m going to speak up so it’s not always the women who have to point it out and they don’t have to solve the problem. You can just say, ‘You keep interrupting her. Let her speak.’”

Male allies in the workforce are also important. Pat East, co-founder and former CEO of Hanapin Marketing (recently acquired by the British performance agency Brainlabs) and executive director of Dimension Mill, says being aware of diversity and inclusion sometimes takes conscious effort.

“We used to have manpower meetings at Hanapin,” he says. “But then someone asked, do we really have to call them ‘manpower’ meetings when there are men and women there? He was very sheepish about asking, but it was important. And now we call them staffing meetings.”

East points out that you can’t change a culture overnight, but you can start making changes today. “If you are at 10% female speakers, get it to 20%,” he says. “Hopefully, you can leapfrog over that, once you realize diversity is important.”

Science and technology are for everyone

STEM encompasses a lot of academic fields and even more professions. The statistics are grim, with women earning fewer than 20% of bachelor’s degrees in computer science and engineering, fewer than 40% in the physical sciences, and fewer than 50% of degrees in mathematics and statistics. The only degree area where women earn more degrees than men are in the psychological, biological, and social sciences.

April Bledsoe is program chair in design technology for Ivy Tech Community College–Bloomington. She graduated with an engineering degree in 2000 and worked in the industry before moving into teaching. She knows things haven’t changed that much in terms of women engineers in the workforce. “Most companies want to say they’re at 20% women, but that’s pushing it,” she says.

She would like to see more women engineers, but she also sees great value in women taking design technology courses as a way to add value to a major outside of STEM.

“I had a student who wasn’t full-time design technology,” Bledsoe says. “She was an IU student, a fashion design major. We teach people how to design and how to make a 3-D object. She’s going to be a pioneer in her field of textile design, of shoe design. What an interesting way to do that, because software is the tool you use.”

Bledsoe says girls who don’t think engineering is for them just need the chance to see that it is. “Get them here, and once they see it, they get excited about it,” she says. “The old way to think about it was that they are going into manufacturing. But now? You’re an innovator and we’re just giving you the tools you need to do it.”

One of the ways Ivy Tech is getting girls interested in engineering is through a summer outreach program funded by the Verizon Foundation in the amount of $150,000. According to Jordan Ferguson, program manager with the Ivy Tech Center for Lifelong Learning and project director for the outreach program, the Rural Girls STEM Camp will offer under-resourced middle school girls the opportunity to experience three consecutive weeks of STEM-based education. Follow-up refresher sessions will be held once a month throughout the academic year.

“We are picking girls and asking them to join,” Ferguson says. “This program is targeted to those who might not have other opportunities.” Fifty girls will be selected the first year; another 100 girls will participate the second year.

The program is completely free, including transportation and lunch. The girls will receive an iPad or other tablet that is theirs to keep after the camp. Bledsoe will be the lead instructor. Topics will include augmented reality/virtual reality, robotics and coding, 3D printing, and entrepreneurship design thinking.

“We’re working with area middle school teachers, with Katy Sparks from MCCSC, with ROI [Regional Opportunity Initiatives],” Ferguson says. “We’re working with all of the people who can be involved to make this the best program it can be. We want to show these girls that there is real support for them and real possibilities.”

“Employers tell me every company is becoming a tech company, whether they know it or not.” –Maureen Biggers

Getting girls interested in STEM subjects—whether they pursue a STEM career or not—is key, says Maureen Biggers. “Employers tell me every company is becoming a tech company, whether they know it or not,” she says. Her advice to young women? “Today it’s not about learning a specific kind of technology that you will use in the workforce but learning how to use an application and then tweaking it. Then learn something new down the road. Computing touches every field and every career.”

That’s why Anne Leftwich, the IU researcher and code.org facilitator, says it’s important to integrate technology into K-12 classes and into every college major.

“Not everyone needs to become a computer scientist, but everyone needs to understand computer science because it is so crucial to our everyday lives,” she says. “Even if you are just a regular citizen, you need to know how [technology] works.”

Biggers, the co-founder of IU’s CEW&T and Serve IT, has a bachelor’s degree in speech pathology and audiology, and master’s and doctoral degrees in higher education administration. She is quick to point out she doesn’t have a background in technology—but she knows technology.

“At my center, we love to work with technology majors, but if you are a psychology major or a history major or study music, study your passion!” Biggers says. “Study your passion. But also learn technology.”

For information on other Ivy Tech STEM summer camps for girls (and boys), visit ivytech.edu/bloomington/cll.

Definitions

STEM: Curriculum based on the idea of educating students in four specific disciplines—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—in an interdisciplinary and applied approach.

Coding and Programming: Computer coding involves the translation of natural (human) language into machine commands. Programming involves coding, but includes planning, design, testing, deployment, and maintenance of the code. Coding can be thought of as a subset of programming.

FORTRAN: Derived from Formula Translation, FORTRAN is a general-purpose programming language that is especially suited to numeric computation and scientific computing.

Gamers: In the context of computers, gamers are people who play (and possibly create) video games.

Digital Citizenship: Digital citizenship refers to the responsible use of technology by anyone who uses computers, the internet, and digital devices to engage with society.