by CRAIG COLEY

The Ku Klux Klan’s iconic white hoods and burning crosses have become symbols of white supremacy, but the Klan’s place in the American consciousness outstrips most people’s understanding. In a new book, Bloomington historian James H. Madison dispels misconceptions about an organization whose membership for a time included one-third of Indiana’s native-born white men. To Madison, a retired professor of history at Indiana University, the story of the Klan is highly relevant today. “Klan-type thinking and Klan-type ideals are still with us,” Madison says. “Maybe even more so.”

Author and editor of several books, including two Indiana state histories, Madison, 76, for many years resisted delving deep into this topic because of its unpleasantness. “What pushed me to do it was that in decades of teaching at IU and speaking around the state and elsewhere, the question I most often got was about the Klan,” Madison says.

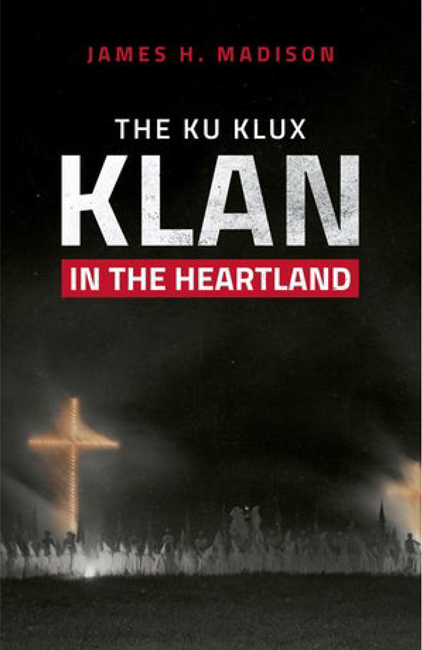

The Klan flourished in three eras: post-Civil War, the 1920s, and the 1960s. Madison’s book, The Ku Klux Klan in the Heartland, published this year by IU Press, tells the story of the Klan in Indiana. It focuses on the 1920s but continues through the 1960s, when Klan members firebombed the Black Market, a Black-owned store on East Kirkwood, and up to the present. The Indiana Klan of the 1920s considered Catholics the biggest threat, followed by Jews and Black Americans. Their overarching belief was in the superiority of the “100% American,” who was white, native- born, and Protestant. They had a weekly newspaper and a political machine that dominated state politics.

Madison dismisses the claim of some writers that most Klan members were uneducated people ignorant of the group’s goals. “The people who joined the Klan were ‘good Hoosiers’ by the definitions of the day,” Madison says. “They were lawyers, protestant ministers, school teachers, factory foremen, retail merchants, church women. Many of the people who joined were true believers. They paid a lot of money in dues and fees and robes and time.”

Madison devotes a chapter to people who resisted the Klan, and concludes by discussing its legacy. “The Klan in the ’20s had a powerful definition of America that attracted a lot of attention,” Madison says. “And right now, we’re in the midst of a debate over the questions, ‘Who is an American?’, ‘What is America?’, ‘What are our ideals?’ It’s really about the future of our democracy.”