By Carmen Siering

Photography by Martin Boling & Jim Krause

As one person interviewed for this story explained, “If you’ve met one Latino … you’ve met one Latino.” That’s because to say someone is Hispanic or Latino tells little except that their family originates from a Spanish-speaking country. “Latino” is an umbrella term, a convenient way of categorizing people with roots in Central or South America, Mexico, or Caribbean countries. However, that’s where generalizations end.

A Latino person may or may not speak Spanish and may or may not have been born outside the United States. In fact, not all Latino people use the word “Latino” at all.

“What we call ourselves is very personal,” says Lillian Casillas, director of La Casa/Latino Cultural Center at Indiana University.

Casillas explains that the 1970 census used the term “Hispanic” for the first time, “but some people didn’t like that because it connects us to Spain and colonization.” Latino became the preferred moniker for many, but not all.

“The person who matters is the one in front of you,” Casillas says. “Let them tell you about themselves. What do they say? ‘I’m Mexican’? Then that’s what matters. ‘I’m from Chicago’? Then that’s what matters. They’ll tell you what they want you to know.”

Latinos in Monroe County

The number of people identifying as Latino has steadily increased in Monroe County over the years. In 2020, the county’s 6,358 Latinos made up 3.7% of the county population, up from 2.9% (4,029) in 2010.

Yllari Briceño is an interpreter, translator, and filmmaker from Peru. That’s where she met her husband, Michael Montesano, an American citizen. In 2013, they moved to the United States when Montesano was accepted into a graduate program at IU.

In 2018, Briceño approached Josefa Madrigal, coordinator for the City of Bloomington Community and Family Resources Department’s Latino Outreach program, with the idea of making a documentary featuring local Latinos. That film, Somos Tus Vecinos (We Are Your Neighbors), is available on the Latino Outreach website and on YouTube. It features 18 members of the Bloomington Latino community discussing their experiences immigrating to and living in the United States.

Casillas was part of the documentary and sums up the way many feel about claiming the Latino label, saying, “I personally consider myself Mexican, but in the U.S., especially in Bloomington, because there is a small community, I consider myself Latina. In that way, I feel part of a bigger group.”

Those interviewed for the documentary make it clear they are proud of being Latino while holding on to the culture of their home countries. Being born in this country is not an impediment to that sense of cultural identity.

Bloomington Police Department (BPD) Officer Gabriela Esquivel was born in Chicago and lived there until she joined the Marine Corps in 2014. She moved to Bloomington in 2019 when she was hired by the BPD. She speaks Spanish and English and serves as a translator for the department. Her identity is very much tied to her parents’ country of origin.

“My mom was born in Mexico and my dad’s parents were born in Mexico,” she says. “I wouldn’t just call myself American; I am Mexican American. We identify more with our Mexican culture. We’re very proud of our roots. Just because I was born in the United States doesn’t mean my culture isn’t from elsewhere.”

Coming Together: The Latino Community Organizes

According to the IU La Casa/Latino Cultural Center records, “In 1971, the Indiana Daily Student put out a call for assistance in forming an office that would address the needs of a growing Latino student body.” In 1973, the IU Office of Latino Affairs was created and its director, Horatio Lewis, helped to establish the La Casa/Latino Cultural Center, a student support center offering tutoring and counseling services.

“It was the direct result of student activism,” Casillas says. “Students were seeking a voice within the university through ethnic studies and through student centers. This was happening across the country, and we were no different. They were looking for someone who would advocate for them as part of the Latino community.” And for nearly 20 years, it was the only resource for the Bloomington Latino community.

Casillas grew up in northwestern Indiana. She came to Bloomington in 1985 as an undergraduate, part of the Groups Scholars Program. After graduating in 1989 with a bachelor’s degree in Spanish, she received a teaching certificate and planned to move to Arizona to teach. Then the director’s position opened at La Casa.

“I thought, ‘Let’s try it for a year,’” she recalls. “A lot of what I do here is teaching. It’s advocating, education, and working with my community, but also the community at large. It’s everything I love. I’ve been here now a total of 27 years.”

As the Latino community within Bloomington grew, it became clear that support was needed for non-university affiliated Spanish speakers. In the mid-1990s, the City of Bloomington Community and Family Resources Department established the Latino Outreach program.

“When it started, newcomers weren’t really connected, and language was an issue,” says Beverly Calender- Anderson, director of the Community and Family Resources Department. “La Casa may have been the only place in the community where they could find help locating resources.”

Yet, by 1999, despite efforts from the City, Casillas noticed increasing numbers of Latinos from off campus seeking assistance from La Casa. A group of concerned university and community women organized to discuss how they might help the growing Latino population in Bloomington.

“When we first started, it was women helping women,” Casillas says. “There were a couple of faculty, some grad students, and community women. We realized we were all helping people in the community and realized we should organize ourselves.”

To coordinate their efforts, the group formed La Central Latina. And working with other agencies, they soon recognized the

need for a Latino community center, which led eventually to the creation of El Centro Comunal Latino, a space within the Monroe County Public Library. There, Latinos had a place to meet to discuss challenges facing their community, a space for events, and a place where those new to the community could secure reliable information about health, safety, and work-related issues.

Because of their overlapping missions and goals, in 2003, La Central Latina merged with and took the name of El Centro Comunal Latino.

Today, El Centro Comunal Latino, La Casa/Latino Cultural Center at IU, and Latino Outreach at City Hall form the foundation of support for Bloomington’s Latino community.

Helping Newbies: El Centro Comunal Latino & HealthNet Bloomington

El Centro Comunal Latino is often the first stop for Latinos new to Bloomington. Located in Room 200 of the public library, 303 E. Kirkwood, El Centro offers a variety of resources, from health education and youth tutoring to document translation and interpretation. But its most significant efforts may be in direct services, including orienting Latino immigrants to their rights and responsibilities in the United States. Maritza Alvarez is El Centro’s director and health coordinator.

“It’s confusing for people who have just arrived,” Alvarez says. “Listening is important. We need to ask, ‘What do you need the most? Where do you want to put your time?’ It’s a lot of cultural work.”

Briceño, the documentary filmmaker, understands how it feels to have to navigate the systems of a new country. When she and her husband moved to the United States from Peru in 2013, they first moved to New Jersey, where her husband’s family lives.

“At the beginning it was kind of a cultural shock,” she says. “I could speak English, but I had never lived in an English-speaking country.”

After four months, the couple moved to Bloomington so her husband could begin his graduate studies. Soon after they arrived, Briceño became pregnant.

“When I was pregnant, we didn’t know about insurance, so we were paying out of pocket, until we just couldn’t pay any more,” she says. “There were a few months when I couldn’t see a doctor. Then I found Volunteers in Medicine [now HealthNet Bloomington Health Center].”

Through the clinic, she was able to finish her prenatal appointments.

Back when HealthNet Bloomington was Volunteers in Medicine (VIM), Shelley Sallee was its clinic manager. She still is. She’s been with the organization since 2008, and explains that years ago, VIM received funding from the Monroe County Health Department to pay for the services of nurse midwives to see prenatal patients at the clinic.

“There is Emergency Medicaid for patients who don’t qualify for any other kind of health care or can’t afford health care and are at an income level of extreme poverty,” Sallee explains. “A part of that is for women who are pregnant and don’t qualify for insurance. Emergency Medicaid will pay for delivery of the baby, but not for prenatal care. At the clinic, we were concerned about that, so we reached out to the health department. And we continue to get funding for prenatal care today.”

Sallee says that Indianapolis-based HealthNet is very supportive of the programs VIM had in place before becoming part of its network.

In addition to OB-GYN services, the clinic offers pediatrics, family practice, behavioral health services, and dental care.

“The patients like it,” Sallee says. “They can come in for their health care, their children’s health care, their parents’ health care. All in one place.”

The clinic has access to interpreters via a phone line, but Sallee says there are several staff members who speak Spanish—including doctors and a nurse, a social worker, and a dental assistant.

Sallee is proud of the way Bloomington organizations work together to ensure patients continue to get help after they leave the clinic.

“We know we aren’t alone in this,” she says. “We reach out to people. When we have patients we know are connected to El Centro, we get their permission in writing to reach out to El Centro so we can work with them. We have a great community that cares about making sure everyone gets care.”

Maritza Alvarez, El Centro’s director, is also its health coordinator. She arrived in New York from the Dominican Republic in 1989. An accountant in her home country, she couldn’t work here because of the language barrier, so she went to school to learn English, then started on the path to a new career.

“When I was an accountant, there was a voice telling me I was wasting my time,” she says. “I always wanted to learn about the human body, but I didn’t know what it took to become a nurse. When I came to the U.S., I was a home health aide, a CNA [certified nursing assistant], an LPN [licensed practical nurse], then an RN [registered nurse].” Through El Centro, Alvarez offers health education programs to the Latino community.

“Latinos have a high incidence of diabetes type 2. One out of two of us,” she says. “So, I organize talks. I find out what they know about diabetes, and I give them educational information. We talk about walking. We walk a lot in our home countries, but we lose that when we come here and get a car. We talk about how to eat, how much to eat. We talk about how to make meal plans.”

Hard Times In The Pandemic

Like many organizations, El Centro’s focus shifted during the pandemic. Jane Walter, an ally to the Latino community, served as El Centro’s director for five years. Her term ended in June 2020. Now she’s a member of its board and continues to oversee fundraising efforts started during the pandemic shutdown.

“With the pandemic, our population was wiped out,” she says. “The people working in restaurants, hotels, child care, in-home elderly care, those were the people who were hit particularly hard. When you have people who are low income and lose their jobs, the impact is huge.”

From April 2020 through mid-August 2021, El Centro raised $121,600 through COVID-relief grants and $55,600 through donations. Sources of funding included United Way of Monroe

County COVID-19 Emergency Relief Fund Phases 1 through 5, a City of Bloomington Jack Hopkins Social Services grant, significant donations from local religious organizations, and a GoFundMe page set up by Indiana University professor of history Ellen Wu, a member of the Bloomington Immigration Task Force. Individual donations included $10,000 from a single couple and the donation of stimulus checks from multiple individuals.

“This outpouring was unbelievably great,” Walter says. “We could see an ocean of need and we were going to drown in it.”

El Centro offered up to $500 per month to each household—families without access to the unemployment benefits and stimulus checks many Americans were receiving at that time. In addition to money, El Centro was doing what it had always done—helping members of the Latino community find resources at existing Bloomington organizations set up to help in times of need.

“There’s more to it than rent,” Walter says. “We were trying to connect them with other groups like the Salvation Army, which continued to see people inside their building throughout the pandemic. St. Paul Catholic Church has a fund for parishioners. I go to that church, so I asked about it. Everyone was trying to be there for people, we were all talking to each other. In the pandemic you just saw people helping people.”

The City Pitches In

One of the people helping Walter coordinate the collection and distribution of the pandemic funds was Josefa Madrigal. She and her eight full-time staff members at the City’s Latino Outreach program work to connect Spanish- and English-speaking Latinos to community resources, offering help finding legal assistance, educational opportunities, seasonal tax help, translation services, and health care. The office organizes the annual City celebration of National Latinx/Hispanic Heritage Month (September 15–October 15) and produces ¡Hola, Bloomington!, a Spanish-language radio program.

Madrigal is also the staff liaison to the City’s Commission on Hispanic and Latino Affairs, which was created by ordinance in 2007 and consists of nine people appointed by either the mayor or common council.

“They identify the issues that are impacting the Latino and Hispanic community, with a focus on health, public safety, education, and cultural awareness,” Madrigal says.

Indiana State Police Captain Ruben Marté, 59, has been a commission member for eight years. Born in the Dominican Republic, Marté says he came to the United States at such a young age he doesn’t remember doing so. He grew up in the South Bronx and moved to Bloomington nearly 30 years ago.

Addressing Policing Concerns

Commission members work together to problem solve. Marté says he had to do that when setting up meetings for different community groups to discuss their concerns with local law enforcement officials. The meetings were held at City Hall prior to the COVID-19 outbreak.

“When we met with the police and the Black community, it was elbow to elbow,” he says. “But then, with the Latino community, there were only two families.”

Shelley Sallee, the HealthNet Bloomington clinic manager, is also on the commission. Marté says the two brainstormed and decided that Latino community members might feel more comfortable if the policing meetings were held at the clinic.

“Then it was elbow to elbow, but that was because Shelley was involved and they trust her,” Marté says. “And when I spoke to them, I wasn’t in uniform. I was in plain clothes.”

A second meeting was held at the clinic, this time with BPD Chief Michael Diekhoff, Monroe County Sheriff Brad Swain, and representatives from the Indiana University Police Department all in attendance. Everyone was in uniform. Marté represented the Indiana State Police.

“I wanted them to see the different uniforms, and I wanted them to know we aren’t Immigration, we aren’t ICE [Immigration, Control, and Enforcement],” he says. “Depending on where you are, that might be the case. But it’s not the case here.”

BPD Chief Michael Diekhoff echoes Marté, saying his department is here to protect people—all people— in the event of a crime.

and other common concerns, as well as conversations with local artists and City officials.

“¡Hola, Bloomington! is steered by volunteers,” Madrigal says. “Some of them have been there for 10 years. The guests don’t have to be Latino, though many are.”

The show isn’t just for adults. Madrigal has worked to create a space for young people on the program. She uses her own life as an example of why she feels this is important.

“I grew up speaking Spanish,” she says. “But I remember when I was at IU, I was speaking Spanish with my friends and a woman said to me, ‘Speak English. This is America.’”

That harsh comment stuck with her. She doesn’t want today’s teenagers to feel any shame associated with their culture.

“I want the teenagers to be proud of who they are, no matter what language they speak,” she says.

“We’re here to serve and to help everyone,” Diekhoff says. “The federal government and Immigration don’t have access to our records. We don’t run checks on people.”

Diekhoff said an unfortunate truth is that undocumented immigrants are sometimes targeted for criminal acts. “We’re aware of that,” he says. “And we’re aware they’re afraid to report it for fear of being deported. We want them to report it so they can navigate the services they need. That’s our concern, not their immigration status.”

‘!Hola Bloomington!’ On The Air

Another way the City’s Latino Outreach program works to keep tabs on the concerns of the Latino community is through the Spanish-language radio program ¡Hola, Bloomington! Airing on WFHB-FM every Friday from 6 to 7 p.m., ¡Hola, Bloomington! features news, entertainment, and public opinion, and frequently has a guest who speaks on a topic of interest submitted by listeners. Past shows have featured discussions about health care, personal finances, and other common concerns, as well as conversations with local artists and City officials.

“¡Hola, Bloomington! is steered by volunteers,” Madrigal says. “Some of them have been there for 10 years. The guests don’t have to be Latino, though many are.”

The show isn’t just for adults. Madrigal has worked to create a space for young people on the program. She uses her own life as an example of why she feels this is important.

“I grew up speaking Spanish,” she says. “But I remember when I was at IU, I was speaking Spanish with my friends and a woman said to me, ‘Speak English. This is America.’”

That harsh comment stuck with her. She doesn’t want today’s teenagers to feel any shame associated with their culture.

“I want the teenagers to be proud of who they are, no matter what language they speak,” she says.

Dual Language Immersion Programs

Born in Chicago, Madrigal moved to Bloomington to attend IU in 2001. She attended the IU Police Academy— graduating in 2006—and worked for the Indiana University Police Department. She graduated from IU in 2008, then served as a patrol officer with the BPD before taking a position as a domestic violence assistant in Indianapolis. Three years later, she took a similar position with the Monroe County Prosecutor’s Office. She started in her current position as staff liaison to the City’s Commission on Hispanic and Latino Affairs in 2016.

“I grew up speaking Spanish at home, but my children didn’t,” Madrigal says. “I was a single mom with my first son, and it was a lot—being in the police academy, going to school. My son had a speech impediment and I got frustrated, so we stuck to English. That was my fault. With the second child, I’m doing better.”

When the opportunity presented itself, she and her husband, Nick Luce, enrolled their younger son in one of the Monroe County Community School Corporation’s (MCCSC) Spanish-English dual language immersion programs.

“When he started in the dual language program, he became more comfortable with the language,” she says. “Before, he wouldn’t speak Spanish at home. Now he has friends who speak Spanish with him, and friends who practice their English with him.”

Two MCCSC elementary schools offer dual language immersion programs—Summit Elementary and Clear Creek Elementary. The programs began with the 2017–18 school year and are funded through grants from the Indiana Department of Education. The program has grown with the students and is now offered in grades K–5. As the students move forward, so will the program, until it is offered all the way through high school.

Students are taught to the same state educational standards, but half of their day is spent learning in Spanish and half in English.

The program helps Spanish-speaking students hold on to their heritage language because it is an additive bilingual program, says Eve Robertson, principal at Clear Creek.

“Oftentimes, an educational program will have an emphasis on teaching students English,” Robertson says. “But in an immersion program, half of their day is spent in their original language, and they learn English better because we are building on the foundation of their Spanish. If they are learning half the day in Spanish, they can continue their academic growth.”

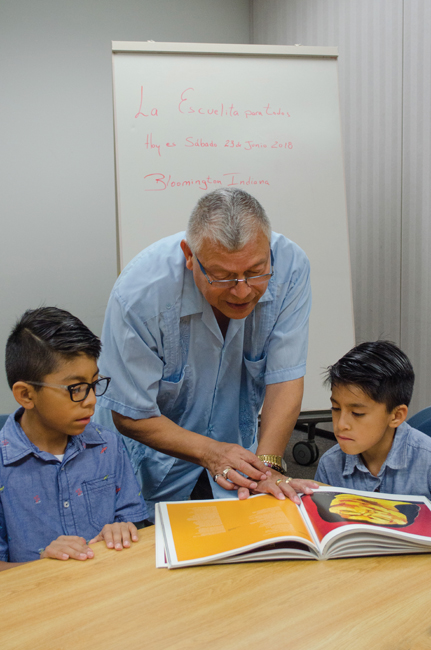

Before the pandemic, El Centro offered La Escuelita Para Todos, the Little School for All, which was held each Saturday. The school offered a dual language program of sorts—while the children learned Spanish, their Spanish- speaking parents learned English. Established by Daniel Soto, La Escuelita shut down during the pandemic, but Soto hopes to have it up and running again in 2022.

El Centro has also joined forces with La Casa to offer tutoring to young Latino students. IU students serve as mentors, offering the younger children a vision of themselves on campus in the future, Casillas says. The program started up again for the 2021–22 school year.

“You have Latino [IU] students on a campus that is predominately white, and the K–12 students are in a predominately white school,” she says. “They are sharing an experience. They can talk about it, and it helps to validate their experience: ‘This isn’t just a Latina student tutoring me, it’s someone who understands and legitimizes my experience.’”

For older MCCSC students, Bloomington High School North has Amigos Club. Elizabeth Sweeney, an English teacher and the club sponsor, says Amigos Club is a mix of Spanish and English speakers, and meetings are bilingual. Everyone is encouraged to speak in whatever language is more comfortable for them.

“It’s a space designed for them, and it promotes unity,” Sweeney says. “We’ve seen a shift in the Latino population in the last four or five years, from a population that was primarily from Mexico and Central America to one from Venezuela and Columbia. Still, they have a shared language and some commonalities and a support system. Even though they are different, the more support we can create for them, the more empowered they can feel in claiming this community for themselves.”

A Bloomington Latino Community

Soto, the founder of La Escuelita Para Todos, has lived and worked in Bloomington for decades, and knows the importance of creating community.

Originally from Costa Rica, Soto moved to the U.S. in 1978 for graduate school. After a short stay in New York City, he moved to Bloomington in 1982. Now retired, he worked for International Services at IU and Latino Outreach. He’s well known among local Latinos for his emphasis on volunteerism and community building.

Soto’s father worked for the diplomatic service in Costa Rica. His family was in Chile at the time of the 1973 coup, then escaped to Argentina, eventually returning to Costa Rica.

“But I wasn’t the same person I was before,” Soto says. “I needed to help other people. A lot of the refugees from Chile would come to the embassy. That’s how my volunteering started, how I became a volunteer with Amnesty International. And when I came to the United States, it was my natural way of doing things. I had to help.”

Teaching other Latinos to help is something Soto has had to do as well.

“I have asked some immigrants about helping someone and they say, ‘I don’t know how,’” Soto says. “And I say, we have to learn.”

Maritza Alvarez, El Centro’s director, explains that both volunteering and accepting help from nonprofit organizations is unheard of in many Latin American countries.

“We don’t have free things like that in our countries,” she says. “If you had a problem and you were my neighbor, I would help you. You don’t go to public places. Latinos are very hard working.”

That work ethic is something that was instilled in Esther Fuentes, banking center manager and assistant vice president at Old National Bank. Her parents divorced when she was 2, and Fuentes lived in her home country of Nicaragua until she came to live with her mother in the United States when she was a teenager in 1992. She’s lived in Bloomington since 2010 and served on El Centro’s boards since then.

“I was brought up working,” Fuentes says. “Whether it was in the house or at the market to bring in some money. It is something we all do there to help the family. When I came here, I moved up in my profession due to that hard work ethic.”

When she started in banking, she began as a teller and decided she would be a manager within three years. It took her three and a half. She’s been in management for 18 years, and feels her job supports other Latinos.

“The Latino community trusts someone who speaks their same language,” she says. “They can see the sense of care.”

Spanish At Church

Sergo Lema would agree with Fuentes. As the Iglesia Hispania pastor at Sherwood Oaks Christian Church, 2700 E. Rogers Road, Lema ministers to the spiritual needs of the Spanish-speaking members of the church.

Lema immigrated to the United States from Bolivia in 2016, moving to Texas with his wife, Sarah Carrasco, to finish his theological studies. The couple, who have two sons ages 6 and 4, moved to Bloomington in May 2019.

Lema says Sherwood Oaks draws a lot of Latino families to its Spanish-language services.

“Probably every Sunday we have 50 or 60 people,” he says. “During the week, maybe 80 or 90 people in Bible studies and groups, meetings and lunches.”

During the Spanish-language Sunday service, the children are sent to the larger, English-language children’s ministry. Lema says he isn’t worried about the children losing their connection to the Spanish language at church—they are exposed to it by default.

“You know, there is a difference between when the English service ends and the Spanish service ends,” Lema says with

a laugh. “We have like an hour and half for chatting. We start talking with everyone!”

‘You’re Welcome Here’

As more Latinos move to Bloomington, there will be more opportunities to make them feel welcome. In just the few years he’s been here, Lema has seen signs of that happening.

“The first time I went to the mall, just two years ago, everything was in English,” he says. “Then the pandemic shut everything down. When we went back, my son said to me, ‘Dad, they’re speaking Spanish [over the sound system].’ And I realized they were trying to make us feel at home in this place. That helped me to start looking for that in other places. And I’ve seen it.”

He says he has noticed more signs in both English and Spanish, and other instances of people trying to break through the language barrier.

“Sometimes people will try to speak Spanish to make me feel better in a restaurant,” he says. “I can speak English, but for the families who only speak Spanish, it is a very good way of saying, ‘You’re welcome here.’”

Latino Population in the U.S.

Before 1980, there were only limited attempts by the United States government to collect data on the country’s Hispanic population, which was relatively small before the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. The 1970 census sampled a small portion of Americans, asking if they were of Mexican, Cuban, Central or South American, or other Spanish origin. The 1980 census asked all Americans the same question. The 2000 census added the word “Latino.”

It’s important to note that the Hispanic/Latino category is described on census forms as an origin, not a race, because Hispanic people can be of any race.

According to the 2020 census, the Latino population in the United States grew by 23% in the last decade. There are 62.1 million Latinos in the United States, making up 18.7% of the total population, up from 16.4% in 2010. Latinos accounted for just over half of the country’s growth since 2010.

Photo Gallery

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Luz Lopez. Photo by Martin Boling

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Fiesta del Otoño. Photo by Jim Krause

Hello, my name is Stella M Saitta, i am from Argentina and I live in Bloomington from 20217. After working 25 years teaching Spanish in California, we moved to Bloomington, and that was the best decision we made! When I wanted to join the LATINO group, where I met many professionals, the pandemic came and everything was ruined. In January 2022, I will again give my help to the Latino Center.