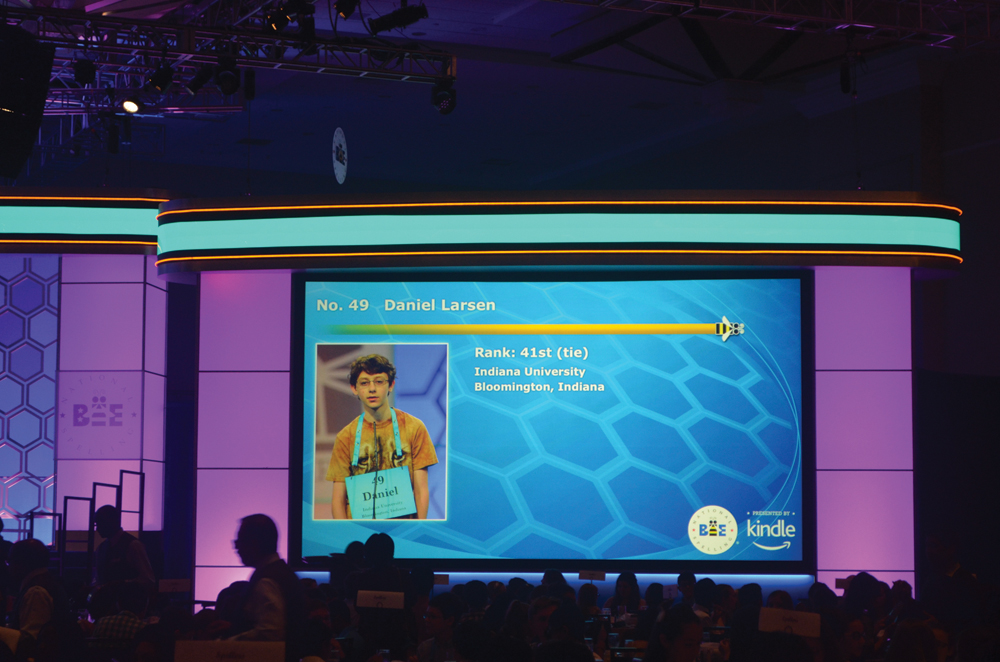

Daniel Larsen at the Scripps National Spelling Bee in Washington, D.C. Courtesy photo

BY PETER DORFMAN

At the end of May, when many of his peers were kicking back and putting seventh grade behind them, Daniel Larsen was traveling to Washington, D.C., to compete in the annual Scripps National Spelling Bee. Daniel earned his shot at the title by winning a five-county regional spelling bee. The Media School at Indiana University and the IU School of Education were the underwriters for the trip.

On the first day of competition, each of the 291 contestants had to spell two words. Daniel was one of 188 who aced both words (his were “rudiments” and “somnolence”), but an earlier written test eliminated him from the 40 who advanced to the final rounds.

That’s okay. At just 13, Daniel has already had his 15 minutes of fame. In February, he became the youngest person ever to have a crossword puzzle accepted by The New York Times. Will Shortz, The Times’ puzzle editor and an IU alum, wrote about Daniel in his column, and the Bloomington media jumped on the Jackson Creek Middle Schooler’s story. Daniel shrugs it all off. “People talked about it for a few days,” he says. “Then it went back to normal.”

All told, he’s sent a total of 20 puzzles to The Times. The others were rejected, but Daniel is unfazed. It took him nine tries to get published. “Will Shortz says he gets 75 submissions a week,” Daniel says. “One in 10 is a good success rate.” He constructs some puzzles solo, and others in collaboration with his sister, Anne, 17. “Building puzzles is much more pleasant when you’re working with someone,” he allows.

Daniel is the son of two IU math professors, Michael Larsen and Ayelet Lindenstrauss. At 12, he built his own crossword-generating software. Like most middle schoolers, he spends a lot of time on the computer, but he shows little interest in gaming. “The computer is a tool to make things,” he says. “The results are tangible. It has a lot of power, but I like the way it bows down to you.”

Because they travel each year to visit Lindenstrauss’ family in Jerusalem, Israel, Daniel has grown up speaking Hebrew. He’s also dabbled in other languages, especially French. He plays classical piano and violin, and he’s a competitive chess and community soccer player. Still, he knows his limits. “I try to be careful,” he says. “You only have so much time.”

Daniel

Congratulations on your selection for sts. My name is Dan Larson. Was in the 40 in 1946. Westinghouse was the sponsor in those years. I have nice memories of my visit to Washington. I had a girlfriend from Denver for 4 days. She had a full house of children and grand children. She passed away about 4 years ago. I have a number of offspring also. I live in Downers Grove, a suburb of Chicago. That is the same town where I grew up. My thanks from my father, college physics teacher and Wayne Guthrie, High School physics teacher who sort of advertised for me., I am 92 now.